Hamas attacked Israel fearing Palestinian reconciliation: Haaretz

Despite the escalation, it seems for now that neither Israel nor Hamas is seeking a broad confrontation.

Yesterday’s mortar barrage on the western Negev is the most extensive operation by Hamas since Operation Cast Lead ended in January 2009. The group has been involved in a few incidents with the Israel Defense Forces since then, but usually on a smaller scale, and it has rarely claimed responsibility.

Yesterday, Hamas publicly announced that its people were behind the latest incident. They said the reason was the Israel Air Force’s attack Wednesday on the Hamas training camp in the ruins of the settlement of Netzarim in which two people were killed. That attack had been precipitated by a Qassam strike a few hours earlier near Sderot.

Hamas said – and to a certain extent justifiably – that Israel had exceeded the unwritten rules of the game. The Qassam had been fired by a marginal Palestinian group, and the accepted response would have been a bombing of empty Hamas offices or an escape tunnel without casualties.

As in the previous rounds of violence, the two sides apparently have more in common than they are willing to admit. Hamas coldly calculated the escalation of fire on Israel yesterday, as Israel did in attacking the Netzarim camp.

Officially, Israel says the bombing of a populated camp was not an extreme departure from an acceptable response. It says it had to remind Hamas of its responsibility to rein in the smaller factions.

In fact, it’s not impossible that the response reflected the general atmosphere after the murder of the Fogel family in Itamar in the West Bank and the interception of the ship carrying missiles from Iran bound for the Gaza Strip the day before.

Despite the escalation, it seems for now that neither Israel nor Hamas is seeking a broad confrontation. The shortening of the periods between attacks – the previous escalation was a month ago, when Islamic Jihad fired a Katyusha at Be’er Sheva – increases the risk that things will spin out of control to a broader campaign against Gaza later in the year.

Hamas says that all it wants is to bring back the status quo on the border with the Gaza Strip. But Palestinian sources in Gaza say they doubt Hamas’ explanation.

The sources say the reason for yesterday’s massive barrage is Hamas’ concerns about Fatah’s calls for reconciliation and unity among Palestinian factions. Last Tuesday, the Hamas prime minister in Gaza, Ismail Haniyeh, called on Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to visit Gaza to reopen discussions on a unity government. Abbas quickly responded that he is ready to come “tomorrow.”

However, Haniyeh’s invitation was issued without the knowledge or approval of Hamas leaders in Damascus and the group’s military wing in Gaza, who see a possible Abbas visit to Gaza as a problem and risk. Reconciliation could lead to elections, which could jeopardize Hamas’ control over the Gaza Strip. A Hamas leader in Damascus, Mohammed Nazzal, said yesterday in an interview on the Hamas website that Abbas’ announcement was mere spin.

Clearly, Hamas has a problem with Abbas’ move and demonstrations throughout the West Bank for reconciliation. While Ramallah is allowing such demonstrations, Hamas is fighting them. It seems that sympathy for Hamas among the Palestinians is waning, and people are daring to protest publicly against it.

If Hamas leaders had thought that the revolution in Egypt and events elsewhere in the Arab world would play into their hands, things now seem more complex. Over the weekend they felt for the first time, even in Damascus – that bastion of Hamas support – the shock waves of the Arab Spring.

Missiles and planes strike Libya: BBC

The UK, US and France have attacked Libyan leader Col Muammar Gaddafi’s forces in the first action to enforce a UN-mandated no-fly zone.

Pentagon officials say the US and the UK have fired more than 110 missiles, while French planes struck pro-Gaddafi forces attacking rebel-held Benghazi.

Col Gaddafi has vowed retaliation and said he would open arms depots to the people to defend Libya.

Cruise missiles hit air-defence sites in the capital, Tripoli, and Misrata.

Continue reading the main story

Analysis

Allan Little

The capital this morning is relatively calm, with traffic moving around as normal, although the atmosphere is quite tense.

At 0230 there was a loud barrage of anti-aircraft fire, but I could hear no sounds of incoming ordnance, and apart from that there’s been no audible sign of the war here in Tripoli.

That is not to say targets on the periphery of the city have not been hit. State TV says 48 civilians have been killed and more than 100 wounded. Last night the speaker of the parliament said hospitals were filling up and that there had been a bombardment of a civilian part of the city, but there’s been no independent confirmation of that.

We’re reporting under restricted circumstances and can’t go out independently. It’s easy to find people swearing undying loyalty to Col Gaddafi – and there’s no doubting their sincerity – but you wonder what’s in the heads of the many millions who do not take part in these angry demonstrations of support for the leader.

Libyan state TV broadcast footage it says showed some of the 150 people wounded in the attacks. It said 48 people had been killed. There was no independent confirmation of the deaths.

Military officials are said to be assessing the damage from the overnight raids before deciding on their next move.

At least 14 bodies were lying in and around the remains of military vehicles which littered the road leading to Benghazi after the French strikes, Reuters reports.

Rebel forces are now heading from Benghazi to the town of Ajdabiya, which has been the scene of fierce fighting in recent days, the agency says.

Hundreds of Col Gaddafi’s supporters have gathered at his Bab al-Aziziyah palace and the international airport to serve as human shields, state TV said.

The AFP news agency reports that bombs were dropped near the palace, which the US also attacked in 1986.

In the early hours of Sunday morning, heavy bursts of anti-aircraft fire arced into the sky above Tripoli and several explosions were heard.

Sources in Tripoli told BBC Arabic that the attacks on the city had so far targeted the eastern areas of Sawani, Airport Road, and Ghasheer. These are all areas believed to host military bases.

The Western forces began their action on Saturday, after Libyan government forces attacked the main rebel-held city of Benghazi – Col Gaddafi’s allies accused the rebels of breaking the ceasefire:

A French plane fired the first shots against Libyan government targets at 1645 GMT on Saturday, destroying military vehicles near Benghazi, according to a military spokesman

At least 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles were fired from US destroyers and submarine, said a Pentagon official

A British submarine and Tornado jets fired missiles at Libyan military targets, the UK Ministry of Defence said

There were also strikes near the western city of Misrata

France has denied Libyan claims to have shot down a French plane

A naval blockade against Libya is being put in place.

“It’s a first phase of a multi-phase operation” to enforce the UN resolution, said US Navy Vice-Adm William E Gortney.

The BBC’s Kevin Connolly, in the rebel-held eastern city of Tobruk, says that once the air-defence systems are taken out, combat aircraft can patrol Libyan airspace more widely and it will then become clear to what extent they will attack Col Gaddafi’s ground forces.

This will determine the outcome of the campaign, he adds.

Russia and China, which abstained from the UN Security Council resolution approving the use of force in Libya, have urged all parties to stop fighting, as has the African Union.

After the missile bombardment and the air strikes, Col Gaddafi made a brief speech calling on people to resist.

“Civilian and military targets in the air and sea will be liable to serious danger in the Mediterranean,” he said.

The Libyan leader called the attacks “a colonialist crusade of aggression. This can lead to open a new crusade war.”

Our correspondent says it is now clear that Col Gaddafi’s strategy is to portray the attacks as an act of colonialist aggression and rally enough of the Libyan people behind him to maintain his grip on power.

‘Legal and right’

US President Barack Obama, speaking during a visit to Brazil, said the US was taking “limited military action” as part of a “broad coalition”.

“We cannot stand idly by when a tyrant tells his people there will be no mercy,” he said.

He repeated that no US ground troops would take part.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron said that launching military action against Libya was “necessary, legal and right”.

The international community was intervening to stop the “murderous madness” of Col Gaddafi, French President Nicolas Sarkozy said.

“In Libya, the civilian population, which is demanding nothing more than the right to choose their own destiny, is in mortal danger,” he warned. “It is our duty to respond to their anguished appeal.”

Canada is also sending warplanes to the region, while Italy has offered the use of its military bases.

Rebels in Benghazi said thousands of people had fled the attack by Col Gaddafi’s forces, heading east, and the UN refugee agency said it was preparing to receive 200,000 refugees from Libya.

Col Gaddafi has ruled Libya for more than 40 years. An uprising against him began last month after the long-time leaders of neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt were toppled.

Is entertaining dictators worse than normalizing apartheid?: The Electronic Intifada

Nada Elia and Laurie King, 3 March 2011

As revolutions continue to sweep the Arab world, and the days of dictators seem numbered, we are learning a lot about the ties and alliances that have long characterized the west’s dealing with tyrants around the globe. “Stability,” apparently, requires us to make deals with the devil. And so we discover that the United States has long known about the human rights abuses of deposed Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, deposed Tunisian president Zine el-Abedine Ben Ali, and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. But it was willing nonetheless not only to turn a blind eye to these, but even to enable and fund, directly or indirectly, oppressive regimes, for the sake of what exactly? Oil? Corporations? The so-called “peace process?” Iraqi “freedom?” Israel’s security?

And as Arab tyrants are challenged, one by one, social media are abuzz with the embarrassing and numerous compliments and kind remarks that western heads of state, academics, pundits, and entertainers have given these deposed dictators. In a typical statement, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, for example, said in 2009: “I really consider President and Mrs. Mubarak to be friends of my family.” Apparently, the Clinton-Mubarak friendship goes back about 20 years. Gaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam, a close friend of Prince Andrew, Queen Elizabeth’s second son and fourth in line to the British throne, has been a guest at Windsor Castle and Buckingham palace. The list is long.

But as the people seem determined to overthrow all those oppressive regimes, liberal Americans are openly questioning the wisdom and morality of “dealing with the devil.” In a highly critical segment on Anderson Cooper’s program AC 360, Cooper, a CNN journalist exhibiting an unusual level of courage and integrity among mainstream American media personalities, called out the various US presidents who have welcomed Gaddafi into their diplomatic circles, even as they acknowledged his tendency towards malice and mental instability, best epitomized by Ronald Reagan’s name for him: “the madman of the desert” (KTH: The West and Gadhafi’s regime,” 24 February 2011).

In that same episode, Cooper was critical of American artists Beyonce, Usher, and Mariah Carey, all three of whom gave private performances for the Gaddafis. Carey apparently received one million dollars for performing four songs for the Gaddafis on New Year in 2009. The following year, it was Beyonce and Usher who graced the Libyan dictator’s New Year’s celebration. Cooper asked why artists would perform for tyrants, and suggested that they donate the money they received to the Libyan people.

The news item was quickly picked up by other media. Rolling Stone magazine also ran an article stating that the music industry is lashing out at these artists, and quoting David T. Viecelli, agent for Arcade Fire and many other acts, as saying “Given what we know about Qaddafi and what his rule has been about, you have to willfully turn a blind eye in order to accept that money, and I don’t think it’s ethical” (Industry Lashes Out at Mariah, Beyonce and Others Who Played for Qaddafi’s Family,” 25 February 2011).

Amid all this uproar, Canadian singer Nelly Furtado announced on Twitter that she would donate to charity a one million dollar fee she received to perform for the Gaddafi family in 2007 (“Nelly Furtado to give away $1 million Gaddafi fee,” Reuters, 1 March 2011).

Those of us who have long been engaged in Palestine justice activism cannot help but notice glaring double-standards in these denunciations of the various deals with devils. And at this critical point in the history of the Arab world, we must request that our readers begin to “connect the dots” throughout the region. Is entertaining dictators a lesser crime than normalizing Israeli apartheid?

Why hold artists accountable for performing at the behest of tyrants, and let them off the hook for whitewashing Israel’s regime which engages in massive human rights abuses, all subsidized by the United States government?

Why not call artists who have performed in Israel, a state which practices a form of apartheid worse than anything the South African apartheid government had ever done? In 1973, the United Nations General Assembly defined the crime of Apartheid as “inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” As Israel’s official policy privileges Jewish nationals over non-Jewish citizens, creating de facto and de jure discrimination against the indigenous Palestinian people, it is hard to dispute that this supposed “democracy” is in reality an apartheid state.

Many of the discriminatory measures Israel practices today were unthought of in apartheid South Africa. In his powerful essay, “Apartheid in the Holy Land,” penned shortly after his return from a visit to the West Bank, Archbishop Desmond Tutu wrote: “I’ve been very deeply distressed in my visit to the Holy Land; it reminded me so much of what happened to us black people in South Africa” (“Apartheid in the Holy Land,” The Guardian, 29 April 2002).

In 2009, a comprehensive study by South Africa’s Human Sciences Research Council confirmed that Israel is practicing both colonialism and apartheid in the occupied Palestinian territories.

That study was inspired by the observations of John Dugard, South African law professor and former UN special rapporteur on human rights in the occupied Palestinian territories, who wrote in 2006: “Israel’s large-scale destruction of Palestinian homes, leveling of agricultural lands, military incursions and targeted assassination of Palestinians far exceeded any similar practices in apartheid South Africa. No wall was ever built to separate blacks and whites.” And no roads were ever built for whites only in South Africa either, while Israel continues to build Jewish-only roads, cutting through the Palestinian landscape.

Israel’s form of apartheid includes the crippling blockade of Gaza; the ongoing seizure of Palestinian land and water sources; construction of the West Bank apartheid wall declared illegal by the International Court of Justice in The Hague; the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Jerusalem; the denial of the rights of Palestinian refugees and discriminatory laws and mounting threats of expulsion against the 1.2 million Palestinians who hold Israeli citizenship.

And as word inevitably gets out, because we are no longer pleading for permission to narrate, but seizing our right to expose these crimes, Israel is hard at work trying to fix its image, without changing the policies and actions that have tarnished that image. As it cements its apartheid policies, Israel is funneling millions of dollars into burnishing its public image as a culturally vibrant, progressive, and thriving democracy.

Among its PR moves is the cultural “Re-Brand” campaign. Israel is intentionally inviting international artists to such “hip” places as Tel Aviv to mask the ugly face of occupation, apartheid, displacement, and dispossession. If we are to hold artists accountable for their choice of performance venues and income sources — as indeed we should — then we should hold them accountable for complicity in normalizing apartheid no less than for entertaining dictators.

In an important article that appeared in The Grio, Lori Adelman also asks: “Why are black pop stars performing at the behest of dictators?” before making the comparison to Sun City, the extravagant whites-only entertainment resort city in apartheid South Africa. And she reminds her readers of the impact of the Artists United Against Apartheid music project, which contributed one million dollars for anti-Apartheid efforts and, most importantly, raised awareness about the global power of artists to influence political discourse on human rights issues (“Why are black pop stars performing at the behest of dictators?,” 24 February 2011).

Today, there is global awareness of Israel’s numerous crimes. And there is a call for artists to boycott Israel, until the country abides by international law. The call was issued in 2005 by the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (www.pacbi.org/). In the US, where we live, the campaign is coordinated by the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel. When we learn of an artist who is planning to perform in Tel Aviv, we contact them, inform them of the reality on the ground (should they need such information), and urge them to reconsider and cancel any concerts they may have scheduled. Many have already done so, including the industry’s biggest names: Carlos Santana, Bono, The Pixies, Elvis Costello and Gil Scott-Heron. Folk legend Pete Seeger also recently announced his support for boycotting Israel.

In what may be the most eloquent statement to date, Costello wrote: “One lives in hope that music is more than mere noise, filling up idle time, whether intending to elate or lament. Then there are occasions when merely having your name added to a concert schedule may be interpreted as a political act that resonates more than anything that might be sung and it may be assumed that one has no mind for the suffering of the innocent. … Some will regard all of this an unknowable without personal experience but if these subjects are actually too grave and complex to be addressed in a concert, then it is also quite impossible to simply look the other way” (“It Is After Considerable Contemplation …,” 15 May 2010).

Today, Artists Against Apartheid are still around, and they are active in promoting the boycott of a country that is practicing apartheid in the 21st century, namely Israel. The question should be, then, if artists boycotted Sun City, shouldn’t they also boycott Tel Aviv? Why the outrage when Beyonce entertains Gaddafi, but not when Madonna, Lady Gaga, Rihanna, and so many more, entertain apartheid in Israel?

Editor’s note: this article originally incorrectly stated that Mariah Carey and Usher had performed in Israel but they have not done so. This version of the article reflects that correction.

Laurie King, an anthropologist, is co-founder of The Electronic Intifada.

Nada Elia is a member of the Organizing Committee of USACBI, the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (Facebook).

Libya: This is only the first step along an unpredictable and hazardous road: The Observer

The durability of the international coalition behind the Libyan intervention will be tested in the crucible of conflict

Andrew Rawnsley

Sunday 20 March 2011

On 14 April 1999, at the height of the Nato intervention to prevent Slobodan Milosevic from brutalising the people of Kosovo, American pilots spotted what that they took to be a column of Serbian paramilitaries moving down a road. The airmen’s error was understandable: video from the gunsight monitors later revealed that the vehicles could easily be mistaken for military trucks from the cockpit of an F-16 flying at screaming speed at an altitude of 15,000 feet. The pilots went for the kill. What they hit was not Serbian forces, but a convoy of tractors hauling trailers packed with refugees. By the time the onslaught was over, the warplanes had killed at least 70 of the civilians that they had been sent to protect.

That was one of several unintended tragedies in the prosecution of an earlier intervention to stop a dictator from taking his bloody revenge on those who had risen up against him. In the end, the Serb forces were driven out of Kosovo, ethnic cleansing was prevented and Slobodan Milosevic was subsequently put on trial at the Hague for war crimes.

But the eventual outcome makes people liable to forget that there were some very bleak stretches during that intervention and many times when politicians and pundits pronounced that it was a terrible failure. During those dark days, critics were clamorous while faint-hearted supporters flaked away. The international coalition formed for that intervention almost fell apart. The prime minister was attacked as a jejune who had blundered into an utterly misconceived conflict. For a while, some around Tony Blair even thought it might cost him his premiership.

As David Cameron commits to his first war, I cite Kosovo not to suggest that it is wrong to act in Libya. I supported the Kosovo intervention. I argued here last week that there is a compelling moral case and one of national interest for taking action in Libya. I recall Kosovo as an example of how military intervention is always freighted with risks, international coalitions are hard to sustain beyond the initial euphoria when they are first assembled, and a military plan almost never survives unaltered after first contact with the enemy. Declaring an intervention is only the first step along a highly hazardous road; the really tough test is bringing it to a successful conclusion.

At the moment, we are only at the opening, relatively easy, chapter of intervention in Libya. This is the acclamatory phase. Public opinion is broadly behind confronting Colonel Gaddafi. So are most of the media. As are the senior voices of the mainstream political parties. This domestic consensus reflects the international one. It was impressive that the United Nations Security Council voted for intervention by 10 votes to nil with 5 abstentions. This was a feat which redounds to the credit of the British diplomats involved in the effort. It was very important that the resolution was co-sponsored by Lebanon, an Arab state, and backed by all three of the African countries on the Security Council. It was significant that the Russians and the Chinese did not wield their vetoes. For the first time, Beijing and Moscow have accepted that it can be legitimate to make protective interventions against tyrannies, an important precedent.

This display of international solidarity has been of great assistance to David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband, all of whom feel the need to demonstrate that intervening in Libya is a very different proposition from the invasion of Iraq. That was a repeated leitmotif of Mr Cameron’s speech to MPs on Friday and of his statements since. He has stressed the regional support for action among Arab states and the legal base provided by the UN resolution. He pointedly told MPs that the attorney-general had advised the cabinet and that counsel had been discussed by ministers – another way of saying this was not Iraq, accompanied by an unsubtle dig at the way in which Tony Blair marched a compliant cabinet to war against Saddam without a proper debate on the legal basis for action.

At this early stage, Mr Cameron has earned some deserved praise for his handling of the first major foreign policy crisis of his premiership. After his Commons statement, Conservative MPs saluted their leader. Nick Clegg and Chris Huhne sat on the front bench, nodding approvingly. A Lib Dem member of the cabinet says proudly: “We have taken as forward a position as the Conservatives. We have argued the same way Paddy Ashdown did over Kosovo. To stand aside in this sort of situation would have been unconscionable.” Iraq has left deep and still not entirely healed wounds in the Labour party. It would have been less risky for Ed Miliband and Douglas Alexander, the shadow foreign secretary, to sit on the sidelines. So they deserve some credit too for putting Labour on the right side when a fascistic dictator threatens slaughter on his own people. Mr Cameron will get a resounding endorsement for his position when MPs vote tomorrow. That will provide some political air cover as the acclamatory phase turns into the much more hazardous implementation phase. He is likely to discover nevertheless how fickle the public, the media and other politicians can be. Some of those who laud him now will be only too quick to lambast him when things don’t go to plan, as they almost certainly won’t.

We will see whether Arab support and participation has depth or is a brittle fig leaf that will soon fall away. The Security Council resolution mandates the use of “all necessary measures” to protect civilians, which is robust and comprehensive by UN standards, and yet still open to multiple interpretations of what this legitimises the coalition to do.

At the heart of the perils ahead stands Colonel Gaddafi, the great survivor among tyrants. He may be mad, but that doesn’t mean he is entirely stupid. He initially responded to the resolution in the way that any averagely crafty dictator might react when he found himself friendless at the UN and confronted by military powers far superior to his own. He declared a ceasefire as if he had suddenly become a reformed character who would not hurt a hair on a civilian’s head. We can be justified in regarding that possibility as being about as likely as discovering that Elvis Presley is alive and well living in the stomach of the Loch Ness monster. Gaddafi is simply adjusting tactics in the face of force majeure.

Continuing attacks on rebel cities yesterday gave the lie to the ceasefire declaration. Even if he does desist from using his mercenaries and heavy weaponry, he will continue to attempt a slow strangulation of Benghazi and the other cities in the rebel east of the country while continuing a vicious suppression of the forces of freedom in Tripoli and other cities in the west. We can expect him to try to reinvent himself from oppressor of his people into victim of western aggression. It is a pretty good bet that he is moving military assets next to hospitals and schools, and planning to use Libyan civilians as human shields for himself and his cronies. He will want to make civilian deaths look like the fault of the west and hope to persuade opinion, especially in the Arab world, that this intervention is not an act of humanity but a war of colonial domination.

The allies will have to conduct operations with extreme care to try to avoid military blunders that will hand him potential propaganda coups. That necessity to act with great precision contends with an imperative to move swiftly. The next few days may prove critical in applying psychological pressure to convince those forces still fighting for Gaddafi to peel away. The longer he has to dig in, the greater the danger that we will end up with a stalemate. Here there is a parallel with Iraq. A no-fly zone was imposed on Saddam Hussein at the end of the first Gulf War in 1990 and Iraq was quasi-partitioned when the west gave special protection to the Kurds in the north. You may remember – I am sure Gaddafi does – that Saddam Hussein nevertheless continued to rule in Baghdad for a further 13 years.

Barack Obama, David Cameron, Nicolas Sarkozy and others have explicitly declared that Gaddafi has to be removed from power if Libya is to have a chance of a future free from tyranny. They are right. It would be a dismal outcome to end up policing a partition: a free eastern Libya while he continues to terrorise the western half of the country. We would be left with a pariah, highly dangerous Gaddafi regime on the southern borders of Europe. The people of Libya will never be truly safe from him until he no longer has the power to do them harm. The logic of the position taken by David Cameron is that this crisis will not be resolved until Gaddafi is gone. But the resolution does not authorise regime change and Nick Clegg felt he needed to remind some of his colleagues of that when the cabinet discussed it on Friday morning.

So the end point of this intervention is uncertain, the enterprise is pregnant with perils, the durability of both domestic support and the international coalition has yet to be tested in the crucible of conflict. The cause is just, but the worst error anyone can make is to imagine that it is likely to be smooth, simple or easy.

Israeli taxes are funding an anti-Arab worldview: Haaretz

When Palestinians ‘incite’ against Israel, this is a matter for international protest, but when Safed’s chief rabbi incites against Arabs, Israeli Jews merely roll their eyes.

By Zvi Bar’el

A burning car creates a luminous blaze. The burning car of an Arab student, by contrast, flickers weaker than a candle. The torching of cars in the criminal underworld is headline stuff. When right-wing extremists torch cars of Arabs in Safed, it’s almost uninteresting, nearly routine.

When Palestinians “incite” against Israel, this is a matter for international protest, or at least for a mighty influx of well-sponsored e-mails by Palestinian Media Watch, which employs translators to trace every tidbit of information that might help prove that the Palestinian Authority, Fatah or any Fatah-associated faction is busily creating a culture of hate against Israel. But when Shmuel Eliyahu, Safed’s chief rabbi, tells a conference that halakhic law demands that a man who rented or sold an apartment to Arabs compensate his neighbors for the drop in their apartments’ value, and that the solution to this problem is encouraging Arabs to emigrate, they merely roll their eyes. Nobody heard and nobody saw.

Nor did anybody hear the same Eliyahu saying in a class in the settlement of Itamar after the murder of the Fogel family that a senior security official asked him to work against any Jewish terrorist activity that might follow the killings. Fogel said he refused: “I told him, if you expect me to stop someone engaging in ‘price tags,’ you’re mistaken. I don’t work for you. But I want to tell you that unless the government takes action, the public will feel a need to take action. And if you don’t act, even if I stand with my arms wide open, I won’t be able to stop those who would act.”

But it would be a big mistake to write off Eliyahu’s words as incitement. He actually reflects an entire worldview, shared by many sections of the public, religious and secular alike, in Israel proper and in the settlements, and among many cabinet and Knesset members. Eliyahu is not creating a new ideology. At most, he’s translating into human language the idea of a “Jewish state” whose borders he is pushing east to the Jordan River.

Eliyahu and his comrades are confidently drawing the new borders of the Jewish state according to the racist principles and fascist values being fleshed out in the Knesset. The map’s general outlines can be easily seen already: They twist and turn around every neighborhood, home, village or city populated by Arabs, and they hug and embrace every settlement and outpost until a blood-chilling map of two colors is produced: One color for territories that should be Arab-free, another for territories currently free of Jews. Each person knows exactly where he should live, and where he doesn’t belong.

The map is being etched by torching Arab student’s cars, terrorism euphemistically labeled “price tag,” preventing the renting of apartments to Arabs, and taking over Arab land in the occupied territories and East Jerusalem. It’s a map aimed at purifying the Jewish camp and preventing Israel from becoming a binational state. This isn’t incitement. It’s an activity subcontracted to Eliyahu and his followers by the Israeli government.

Eliyahu is part of his people, not only in Safed but throughout the country, whose authorities allow him and his ilk to speak the way they do at the public’s expense. No parliamentary commission is needed to trace the funding sources for Eliyahu and the Safed rabbinate and to find out who pays for his hate-mongering. He’s not backed by conservative organizations from abroad, like those that support Palestinian Media Watch, or evangelical charities that fund the purchase of homes in East Jerusalem. His support comes from Israeli taxpayer money.

There’s no way of explaining the financial and ideological support received by Eliyahu but to assume he’s simply offering a practical way of carrying out the government’s hidden desires. If someone in the cabinet thought that Eliyahu and his acolytes didn’t represent him, he would have offered, for example, to compensate the Arab students for their burned cars, as any terrorism victim is compensated. There’s no way to describe what happened other than terrorism. Someone who’s only willing to roll his eyes or denounce Eliyahu’s words as incitement misses the most important thing: The state itself is an accomplice.

Relief will fade as we see the real impact of intervention in Libya: The Guardian

Welcome though it seems on humanitarian grounds, there are six serious problems with this UN resolution

Abdel al-Bari Atwan

Friday 18 March 2011

The first reaction was relief. The UN security council resolution 1973 authorising foreign intervention in Libya was held up as an attempt to protect the Libyan rebels and alleviate their suffering, and who would not welcome that? Who would not want to stop a bully intent on “wiping out” those who oppose him? But any relief should be tempered by serious misgivings.

First, what motives lie behind this intervention? While the UN was voting to impose a no-fly zone in Libya, at least 40 civilians were killed in a US drone attack in Waziristan in Pakistan. And as I write, al-Jazeera is broadcasting scenes of carnage from Sanaa, Yemen, where at least 40 protesters have been shot dead. But there will be no UN no-fly zone to protect Pakistani civilians from US attacks, or to protect Yemenis. One cannot help but question the selective involvement of the west in the so-called “Arab spring” series of uprisings.

It is true that the US was reluctant to act and did so only after weeks of indecision. Unwilling to become embroiled in another conflict in the region where it would be perceived as interfering in the affairs of a sovereign state, Obama wisely insisted on a high level of Arab and Muslim involvement. At first the signs were good: the Arab League endorsed the move last week, and five member states seemed likely to participate. But that has been whittled down to just Qatar and the UAE, with Jordan a possible third. This intervention lacks sufficient Arab support to give it legitimacy in the region.

The US was worried about the cost of military action, too, given its ailing economy. Abdel Rahman Halqem, the Libyan ambassador to the UN, has told me that Qatar and the UAE have agreed to foot most of the bill for the operation. And what is the motive of these autocratic states: to protect the Libyan people, a grudge against Gaddafi, or to bind the US further into the region?

So this is the second problem: the main players in this intervention are western powers led by Britain and France with US involvement likely. If Libya’s neighbours, Egypt and Tunisia, were playing the leading role that would be something to celebrate. Democratic countries helping their neighbours would have been in the spirit of the Arab uprisings, and would have strengthened the sense that Arabs can take control of their future. It could have happened too: Egypt gets $1.3bn of US military aid a year. Diplomatic pressure by Hillary Clinton could have brought that mighty war horse into the arena, or at least encouraged Egypt to arm the rebels. Instead, an Egyptian foreign ministry spokesperson stated categorically on Wednesday: “No intervention, period.”

The third problem is that, although he is often dismissed as mad, Gaddafi is a master strategist and this intervention plays into his hands. He quickly announced a ceasefire in response, which was claimed by some as an early victory for the UN resolution; in fact, it both deflates the UN initiative and allows Gaddafi to appear reasonable. Meanwhile, a ceasefire at this point suits Gaddafi: under its cover, the secret police can get to work. Similarly, Gaddafi accepted the earlier arms embargo: again, this apparent concession suited him. His regime has sophisticated weaponry, whereas the rebels have few arms.

Gaddafi knows how to play the Arab street, too. At the moment he has little, if any, public support; his influence is limited to his family and tribe. But he may use this intervention to present himself as the victim of post-colonialist interference in pursuit of oil. He is likely to pose the question that is echoing around the Arab world – why wasn’t there a no-fly zone over Gaza when the Israelis were bombarding it in 2008/9?

Unlike in Tunisia and Egypt, the uprising in Libya quickly deteriorated into armed conflict. Gaddafi could question whether those the UN is seeking to protect are still “civilians” when engaged in battle, and suggest instead that the west is taking sides in a civil war (where the political agenda of the rebels is unknown).

And what of the long-term impact of this intervention on Libya, and the world? Here lies yet another concern. Libya may end up divided into the rebel-held east and a regime stronghold in the rest of the country which would include the oil fields and the oil terminal town al-Brega. There is a strong risk, too, that it will become the region’s fourth failed state, joining Iraq, Afghanistan and Yemen. And that ushers in another peril. Al-Qaida thrives in such chaos; it played a key role in the Iraqi and Afghan insurgencies and is based in Yemen – and it may enter Libya, too. Several of Bin Laden’s closest associates are Libyan, and Gaddafi is no stranger to terror groups – the Abu Nidal Organisation found a safe haven in Libya from 1987 to 1999. Gaddafi has also threatened to attack passenger aircraft and shipping in the Mediterranean.

Fifth, there is no guarantee that military intervention will result in Gaddafi’s demise. In 1992, the UN imposed two no-fly zones in Iraq – to protect the Kurds in the north and the Shi’a in the south. Saddam remained in power for another 11 years and was only toppled after an invasion. To date, over a million civilians have died in Iraq. The international community has a duty to ensure that this sorry history is not repeated in Libya.

Finally, there is the worry that the Arab spring will be derailed by events in Libya. If uprising plus violent suppression equals western intervention, the long-suffering Arab subjects of the region’s remaining autocrats might be coerced into sticking with the status quo.

The Libyan people face a long period of violent upheaval whatever happens. But it is only through their own steadfastness and struggle that they will finally win the peaceful and democratic state they long for.

Syria to release children who sparked anti-government protests: Haaretz

Demonstrations erupted in the southern city of Deraa after 15 children were arrested for writing freedom slogans inspired by Egypt, Tunisia unrest.

Syrian authorities said on Sunday they will release 15 children whose arrest helped fuel protests in the southern city of Deraa during which security forces killed four civilians.

An official statement said the children, who had written freedom slogans on the walls inspired by the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, will be released immediately.

On Friday, eyewitnesses claimed that Syrian security forces killed five demonstrators in Deraa as they took part in a peaceful protest demanding political freedom and an end to corruption in Syria.

Syrian state media says security forces dispersed protesters in two towns in the most serious unrest in years in one of the Mideast’s most repressive states.

Several thousand protesters chanted “God, Syria, Freedom” and other anti-corruption slogans, accusing the family of the president of corruption, when they were shot dead by security forces who were reinforced with troops flown in by helicopters, a resident said.

Amateur video footage posted Friday on YouTube and Twitter shows large groups of protesters in several cities throughout Syria but its authenticity could not be immediately be independently confirmed.

State television said at the time that some infiltrators in the town of Deraa caused chaos and riots and smashed cars and some property before they were chased off by riot police. It says a similar demonstration in the coastal town of Banyas was dispersed without incident.

One amateur video showed what appeared to be show Syrian government trucks spraying water on marchers. Two others purport to show several thousand men gathering in the cities of Homs and Baniyas.

Japan and Israel: Two ways of dealing with disaster: Haaretz

Five days suffice to shatter some stereotypes and to arouse sympathy, compassion and admiration for the Japanese.

By Gideon Levy

The pictures haunt you even after returning from Japan, and they refuse to let go. The paralyzed old man barely dragging the ruins of his life, stuffed into plastic bags, to the garbage pile at the entrance of his destroyed house. The couple carrying Momo, their beloved dog, whom they saved from the tsunami. The silently weeping old woman whose grandson rescued her from the inferno and who came home to find she has no home. The awful silence over the villages along the ocean, which is broken only by the sound of digging shovels and seagulls’ screams. There is a heavy unease in the world’s largest city. It seems desolate.

Five days in the land of ruins and horror on a first visit to Japan are not enough to know the Land of the Rising Sun, which trembled and then was flooded, burned and irradiated. But those days sufficed to shatter some stereotypes and to arouse sympathy, compassion and admiration for the Japanese.

I fell in love with the Japanese people at first sight. They demonstrated a resonating silence, showing their dignity, their restraint, their acceptance of the worst disaster. The way they handled it was awe-inspiring. I saw their astonishing kindness toward the stranger, a kind of inexplicable apology, as though they were each personally responsible for the earthquake and all that followed. They were sincerely concerned for the visitor who happened to be in their country and ready to assist him, on city streets, the underground or walking the debris of the beaches. I saw them offering help to each other and the mutual aide extended among neighbors and relatives in poor villages. Last week, I saw a noble nation in Japan.

For Israelis, it would have been inconceivable. Anyone coming from the land of fears, real and imagined, excessive and inflamed – a national disaster every day, catastrophe every hour – is overwhelmed by the Japanese composure and restraint in the face of terrifying calamity. Any thought of the Japanese as strange, as advanced, mute and unfeeling machines, was way off base.

I tried to imagine how Israelis would handle such events. True, the Japanese lack what we are so good at – improvisation, resourcefulness and initiative. But reserve is no less vital than improvisation in times of trouble. The restraint was impressive in Japan. The media did not cynically inflame emotions and fears. The masses in Tokyo attempted to go about their routine despite the evident collapse of routine.

There were orderly lines at the gas stations, even when people had to wait two hours for the 10-liter allocation; there was voluntary economizing on the use of electricity, understanding at the sight of the empty supermarket shelves and no shopping frenzy. There was silence in the underground cars as a loudspeaker announced another aftershock; a lack of panic at the check-in counters at Narita International Airport near Tokyo and large railway stations.

It’s impressive, it commands respect and increases one’s compassion and sympathy. Not that there is a lack of horror – Tokyo is frightened of what is to come. Not that the Japanese are complacent about their disaster, nor are they ignoring or repressing it. They bear it all with stoic acceptance – the fishermen whose boat was hurled to the shore; the villagers whose houses shivered and were flooded; the people whose world collapsed and are now burrowing in the mud to salvage the remains.

Everyone is reserved and self-controlled. Nobody complains, nobody lays blame. A stranger, especially an Israeli, is unable to grasp it. From distant Tel Aviv, I write with an aching heart: Fukushima, my love, may the sun rise on you.

Israel: The eroding consensus”: Al Jazeera English

Most influential Jewish American journalist says it is time for US to stop telling Israelis what they want to hear.

MJ Rosenberg

David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker, is arguably the most influential Jewish American journalist.

Now 50, Remnick became editor at 37 after an impressive career covering the collapse of the Soviet Union for the Washington Post. His book about that incredible period, Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire, won a Pulitzer in 1994.

Remnick believes that fear is misplaced and that Obama should think big despite the pressure from the donors and White House aides mired in the status quo.

Over the years he has written about Israel and the Palestinians with some regularity. Although he claims no special expertise in the area (other than being a strongly identifying Jew), his editor’s “comments” indicate that he knows the issue well.

In fact, his pieces are usually far more sophisticated than the news and opinion pieces that the supposed experts regularly produce for the prestige newspapers and journals.

Over Remnick’s past 13 years as editor of The New Yorker, his attitudes toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have evolved. In the early years, Remnick’s views were decidedly mainstream.

Though no Likudnik, he did give Israel the benefit of the doubt in most situations. Back then, he clearly believed that although Israel often blundered, even badly, it still was sincerely seeking peace. Of course, holding those views was significantly easier a decade or two ago than it is today.

Today those views seem only to be held by either true believers (the “Israel can do no wrong” crowd) or politicians determined to ingratiate themselves with donors whose politics can be summed up as “Israel First”.

There aren’t a whole lot of those donors but it doesn’t take very many to intimidate politicians. And intimidated they are.

But established journalists like Remnick don’t have to be intimidated (although ingratiating oneself with rich and powerful people is not an unknown phenomenon among writers).

Trailblazers

Today Remnick is treading the path blazed last year by Peter Beinart, another influential Jewish American writer who had been editor of The New Republic at 24.

A year ago, Beinart broke with the AIPAC crowd with a blockbuster piece in The New York Review of Books explaining how the combination of right-wing Israeli policies and the mindless chauvinism of AIPAC and its allies had succeeded in alienating young Jews from Israel.

Beinart’s piece enraged the pro-Israel establishment, although it knew, from its own surveys, that identification with Israel is strongest among those in their 80s and then drops precipitously among the now-ageing “baby boomers” and their kids. (One Ivy Leaguer recently told me that even J Street is a hard sell among Jewish kids. As for AIPAC, forget about it. In fact, any passion for Israel at all makes you pretty much an outlier.)

A year later, David Remnick has crossed Beinart’s Rubicon. In a “Talk of the Town” essay in his magazine, Remnick definitively asserts that it is time for the United States to put a comprehensive peace plan (exchanging the territories for peace) on the table and to push it to fruition.

He writes that the Obama administration obviously knows this, but is simply afraid of the implications for “domestic politics”. Remnick believes that fear is misplaced and that Obama should think big despite the pressure from the donors and White House aides mired in the status quo.

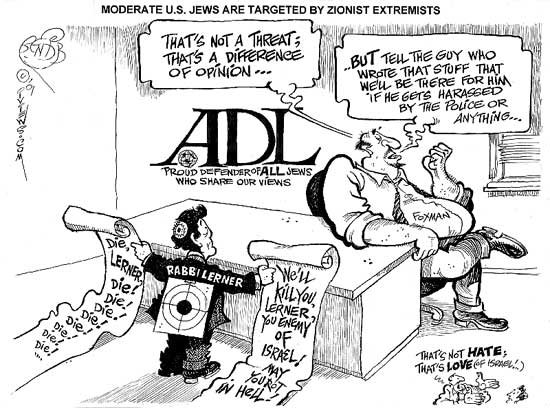

For decades, AIPAC, the Anti-Defamation League, and other such right-leaning groups have played an outsized role in American politics, pressuring members of congress and presidents with their capacity to raise money and swing elections.

But democratic presidents in particular should recognize that these groups are hardly representative and should be met head on.

Obama won seventy-eight per cent of the Jewish vote; he is more likely to lose some of that vote if he reverses his position on, say, abortion than if he tries to organise international opinion on the Israeli-Arab conflict.

However, some senior members of the administration have internalised the political restraints that they believe they are under, and cannot think beyond them. Some, like Dennis Ross, who has served five presidents, can think only in incremental terms.

This is strong stuff, especially when it comes from David Remnick. But it isn’t all.

Netanyahu’s ‘chilling’ influence

A sizeable chunk of the piece is devoted to Remnick’s explanation of why it is silly to expect prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu to abandon his decades-long commitment to the occupation of the Palestinian territories. The thinking goes that:

Just as Nixon set aside decades of Cold War ideology and red-baiting in the interests of practical global politics, Netanyahu would transcend his own history, and his party’s, to end the suffering of a dispossessed people and regain Israel’s moral standing.

Not going to happen, writes Remnick. He believes that the reason is the influence of Netanyahu’s 101-year-old father, Benzion Netanyahu. Remnick tells of a meeting he had with the prime minister’s father, writing that the elder Netanyahu “invited me to his house for lunch, and I am not sure that I have ever heard more outrageously reactionary table talk. The disdain for Arabs, for Israeli liberals, for any Americans to the left of the neoconservatives was chilling.”

Add to that a “coalition government that includes anti-democratic, even proto-fascistic ministers, such as Avigdor Lieberman,” and it is clear that Obama’s sweet talk has not a chance of accomplishing anything.

And that is why Obama has to act decisively and without waiting for permission from AIPAC, Dennis Ross, or the Democratic party’s fundraisers.

The importance of an Obama plan is not that Netanyahu accept it right away; the Palestinian leadership, which is weak and suffers from its own issues of legitimacy, might not embrace it immediately, either.

Rather, it is important as a way for the United States to assert that it stands not with the supporters of Greater Israel but with what the writer Bernard Avishai calls “Global Israel”, the constituencies that accept the moral necessity of a Palestinian state and understand the dire cost of Israeli isolation.

Remnick concludes that it is time for the United States to stop telling the Israelis what they want to hear, and start telling them what almost all policy-makers actually believe.

A friend in need…

If America is to be a useful friend, it owes clarity to Israel, no less than Israel and the world owe justice – and a nation – to the Palestinian people.

A few years ago, there is no chance that either David Remnick or Peter Beinart would be saying these things. And a few years before that they wouldn’t even be advocating a Palestinian state at all. And before that it wasn’t even safe to talk about a discrete Palestinian people.

But it’s all changing for two reasons. First, at long last, it is common and uncontroversial knowledge that the Palestinian people have suffered mightily at the hands of Israel, with the support of the United States.

Second, it has become abundantly clear that Israel’s isolation is increasing at such a rapid rate (Turkey and Egypt distancing themselves from Israel in a single year) that the continuation of the occupation (and the conflict that emanates from it) threatens the existence of Israel itself.

That is why there will be more Remnicks and more Beinarts. Not because influential Americans like them are indifferent to Israel’s survival. But because they aren’t.

MJ Rosenberg is a Senior Foreign Policy Fellow at Media Matters Action Network.