Helen Thomas and the moral failure of US liberals: The Electronic Intifada

Jonathan Cook, 10 June 2010

The ostracism of Helen Thomas, the doyenne of the White House press corps, over her comment that Jews should “get the hell out of Palestine” and “go home” to Poland, Germany, America and elsewhere is revealing in several ways. In spite of an apology, the 89-year-old has been summarily retired by the Hearst newspaper group, dropped by her agent, spurned by the White House, and denounced by long-time friends and colleagues.

Thomas earned a reputation as a combative journalist, at least by American standards, with a succession of administrations over their Middle East policies, culminating in Bush officials boycotting her for her relentless criticisms of the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. But the reaction to her latest remarks suggest that, if there is one topic in American public life on which the boundaries of what can and cannot be said are still tightly policed, it is Israel.

Undoubtedly, Thomas’ opinions, as she expressed them in an unguarded moment, were inappropriate and required an apology. It is true, as she says, that Palestine was occupied and the land taken from the Palestinians by Jewish immigrants with no right to it barring a Biblical title deed. But 62 years on from Israel’s creation, most Jewish citizens have no home to go to in Poland and Germany — or in Iraq and Yemen, for that matter. There is also an uncomfortable echo in her words of the chauvinism underpinning demands from some Jews — and many Israelis — that Palestinians should “go home to the 22 Arab states.”

But Thomas did apologize and, after that, a line ought to have been drawn under the affair — as it surely would have been had she made any other kind of faux pas. Instead, she has been denounced as an anti-Semite, even by her former friends.

The reasoning of one, Lanny Davis, counsel to the White House in the Clinton administration, was typical. Davis, who said he previously considered himself “a close friend,” asked whether anyone would be “protective of Helen’s privileges and honors if she had been asking Blacks to return to Africa, or Native Americans to Asia and South America, from which they came 8,000 or more years ago?”

It is that widely-accepted analogy, appropriating the black and Native American experience in a wholly misguided way, that reveals in stark fashion the moral failure of American liberals. In their blindness to the current relations of power in the US, most critics of Thomas contribute to the very intolerance they claim to be challenging.

Thomas is an Arab-American, of Lebanese descent, whose remarks were publicized in the immediate wake of Israel’s lethal commando attack on a flotilla of aid ships trying to break the siege of Gaza. Unlike most Americans, who were half-wakened from their six-decade Middle East slumber by the killing of at least nine Turkish activists, Thomas has been troubled by the Palestinians’ plight for much of her long lifetime.

She was in her late twenties when Israel ethnically cleansed three-quarters of a million Palestinians from most of Palestine, a move endorsed by the fledgling United Nations. She was in her mid-forties when Israel took over the rest of Palestine and parts of Egypt and Syria in a war that dealt a crushing blow to Arab identity and pride and made Israel a favored ally of the US. In her later years she has witnessed Israel’s repeated destruction of Lebanon, her parents’ homeland, and the slow confinement and erasure of the neighboring Palestinian people. Both have occurred under a duplicitous American “peace process” while Washington has poured hundreds of billions of dollars into Israel’s coffers.

It is therefore entirely understandable if, despite her own personal success, she feels a simmering anger not only at what has taken place throughout her lifetime in the Middle East but also at the silencing of all debate about it in the US by the Washington elites she counted as friends and colleagues.

While she has many long-standing Jewish friends in Washington — making the anti-Semite charge implausible — she has also seen them and others promote injustice in the Middle East. Doubtless she, like many of us, has been exasperated at the toothless performance of the press corps she belongs to in holding the White House to account in Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Lebanon and Israel-Palestine.

It is with this context in mind that we can draw a more fitting analogy. We should ask instead: how harshly should Thomas be judged were she a black professional who, seeing yet another injustice like the video of Rodney King being beaten to within an inch of his life by white policemen, had said white Americans ought to “go home to Europe?”

This analogy accords more closely with the reality of power relations in the US between Arabs and Jews. Thomas is not a representative of the oppressor white man disrespecting the oppressed black man, as Davis suggests; she is the oppressed black man hitting back at the oppressor. Her comments shocked not least because they denied an image that continues to dominate in modern America of the vulnerable Jew, a myth that persists even as Jews have become the most successful minority in the country.

Thomas let her guard down and her anger and resentment show. She generalized unfairly. She sounded bitter. She needed to — and has — apologized. But she does not deserve to be pilloried and blacklisted.

Israel’s Greatest Loss: Its Moral Imagination: Haaretz

If a people who so recently experienced such unspeakable inhumanities cannot understand the injustice and suffering its territorial ambitions are inflicting, what hope is there for the rest of us?

By By Henry Siegman

Following Israel’s bloody interdiction of the Gaza Flotilla, I called a life-long friend in Israel to inquire about the mood of the country. My friend, an intellectual and a kind and generous man, has nevertheless long sided with Israeli hardliners. Still, I was entirely unprepared for his response. He told me—in a voice trembling with emotion—that the world’s outpouring of condemnation of Israel is reminiscent of the dark period of the Hitler era.

He told me most everyone in Israel felt that way, with the exception of Meretz, a small Israeli pro-peace party. “But for all practical purposes,” he said, “they are Arabs.”

Like me, my friend personally experienced those dark Hitler years, having lived under Nazi occupation, as did so many of Israel’s Jewish citizens. I was therefore stunned by the analogy. He went on to say that the so-called human rights activists on the Turkish ship were in fact terrorists and thugs paid to assault Israeli authorities to provoke an incident that would discredit the Jewish state. The evidence for this, he said, is that many of these activists were found by Israeli authorities to have on them ten thousand dollars, “exactly the same amount!” he exclaimed.

When I managed to get over the shock of that exchange, it struck me that the invocation of the Hitler era was actually a frighteningly apt and searing analogy, although not the one my friend intended. A million and a half civilians have been forced to live in an open-air prison in inhuman conditions for over three years now, but unlike the Hitler years, they are not Jews but Palestinians. Their jailers, incredibly, are survivors of the Holocaust, or their descendants. Of course, the inmates of Gaza are not destined for gas chambers, as the Jews were, but they have been reduced to a debased and hopeless existence.

Fully 80% of Gaza’s population lives on the edge of malnutrition, depending on international charities for their daily nourishment. According to the UN and World Health authorities, Gaza’s children suffer from dramatically increased morbidity that will affect and shorten the lives of many of them. This obscenity is a consequence of a deliberate and carefully calculated Israeli policy aimed at de-developing Gaza by destroying not only its economy but its physical and social infrastructure while sealing it hermitically from the outside world.

Particularly appalling is that this policy has been the source of amusement for some Israeli leaders, who according to Israeli press reports have jokingly described it as “putting Palestinians on a diet.” That, too, is reminiscent of the Hitler years, when Jewish suffering amused the Nazis.

Another feature of that dark era were absurd conspiracies attributed to the Jews by otherwise intelligent and cultured Germans. Sadly, even smart Jews are not immune to that disease. Is it really conceivable that Turkish activists who were supposedly paid ten thousand dollars each would bring that money with them on board the ship knowing they would be taken into custody by Israeli authorities?

That intelligent and moral people, whether German or Israeli, can convince themselves of such absurdities (a disease that also afflicts much of the Arab world) is the enigma that goes to the heart of the mystery of how even the most civilized societies can so quickly shed their most cherished values and regress to the most primitive impulses toward the Other, without even being aware they have done so. It must surely have something to do with a deliberate repression of the moral imagination that enables people to identify with the Other’s plight. Pirkey Avot, a collection of ethical admonitions that is part of the Talmud, urges: “Do not judge your fellow man until you are able to imagine standing in his place.”

Of course, even the most objectionable Israeli policies do not begin to compare with Hitler’s Germany. But the essential moral issues are the same. How would Jews have reacted to their tormentors had they been consigned to the kind of existence Israel has imposed on Gaza’s population? Would they not have seen human rights activists prepared to risk their lives to call their plight to the world’s attention as heroic, even if they had beaten up commandos trying to prevent their effort? Did Jews admire British commandos who boarded and diverted ships carrying illegal Jewish immigrants to Palestine in the aftermath of World War II, as most Israelis now admire Israel’s naval commandos?

Who would have believed that an Israeli government and its Jewish citizens would seek to demonize and shut down Israeli human rights organizations for their lack of “patriotism,” and dismiss fellow Jews who criticized the assault on the Gaza Flotilla as “Arabs,” pregnant with all the hateful connotations that word has acquired in Israel, not unlike Germans who branded fellow citizens who spoke up for Jews as “Juden”? The German White Rose activists, mostly students from the University of Munich, who dared to condemn the German persecution of the Jews (well before the concentration camp exterminations began) were also considered “traitors” by their fellow Germans, who did not mourn the beheading of these activists by the Gestapo.

So, yes, there is reason for Israelis, and for Jews generally, to think long and hard about the dark Hitler era at this particular time. For the significance of the Gaza Flotilla incident lies not in the questions raised about violations of international law on the high seas, or even about “who assaulted who” first on the Turkish ship, the Mavi Marmara, but in the larger questions raised about our common human condition by Israel’s occupation policies and its devastation of Gaza’s civilian population.

If a people who so recently experienced on its own flesh such unspeakable inhumanities cannot muster the moral imagination to understand the injustice and suffering its territorial ambitions—and even its legitimate security concerns—are inflicting on another people, what hope is there for the rest of us?

Henry Siegman, director of the U.S./Middle East Project, is a visiting research professor at the Sir Joseph Hotung Middle East Program, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He is a former Senior Fellow on the Middle East at the Council on Foreign Relations and, before that, was national director of the American Jewish Congress from 1978 to 1994.

Victimhood is not an excuse for Israeli injustice: J Cook

Jonathan Cook

The National, June 09. 2010

Why are Israelis so indignant at the international outrage that has greeted their country’s lethal attack last week on a flotilla of civilian ships taking aid to Gaza?

Israelis have not responded in any of the ways we might have expected. There has been little soul-searching about the morality, let alone legality, of soldiers invading ships in international waters and killing civilians. In the main, Israelis have not been interested in asking tough questions of their political and military leaders about why the incident was handled so badly. And only a few commentators appear concerned about the diplomatic fall-out.

Instead, Israelis are engaged in a Kafkaesque conversation in which the military attack on the civilian ships is characterised as a legitimate “act of self-defence”, as Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called it, and the killing of nine aid activists is transformed into an attempted “lynching of our soldiers” by terrorists.

Benny Begin, a government minister whose famous father, Menachem, became an Israeli prime minister after being what today would be called a terrorist as the leader of the notorious Irgun group, told BBC World TV that the commandos had been viciously assaulted after “arriving almost barefoot”. Ynet, Israel’s most popular news website, meanwhile, reported that the commandos had been “ambushed”.

This strange discourse can only be deciphered if we understand the two apparently contradictory themes that have come to dominate the emotional landscape of Israel. The first is a trenchant belief that Israel exists to realise Jewish power; the second is an equally strong sense that Israel embodies the Jewish people’s collective experience as the eternal victims of history.

Israelis are not entirely unaware of this paradoxical state of mind, sometimes referring to it as the “shooting and crying” syndrome.

It is the reason, for example, that most believe their army is the “most moral in the world”. The “soldier as victim” has been given dramatic form in Gilad Shalit, the “innocent” soldier held by Hamas for the past four years who, when he was captured, was enforcing Israel’s illegal occupation of Gaza.

One commentator in Israel’s Haaretz newspaper summed up the feelings of Israelis brought to the fore by the flotilla episode as the “helplessness of a poor lonely victim, confronting the rage of a lynch mob and frantically realising that these are his last moments”. This “psychosis”, as he called it, is not surprising: it derives from the sanctified place of the Holocaust in the Israeli education system.

The Holocaust’s lesson for most Israelis is not a universal one that might inspire them to oppose racism, or fanatical dictators or the bullying herd mentality that can all too quickly grip nations, or even state-sponsored genocide.

Instead, Israelis have been taught to see in the Holocaust a different message: that the world is plagued by a unique and ineradicable hatred of Jews, and that the only safety for the Jewish people is to be found in the creation of a super-power Jewish state that answers to no one. Put bluntly, Israel’s motto is: only Jewish power can prevent Jewish victimhood.

That is why Israel acquired a nuclear weapon as fast it could, and why it is now marshalling every effort to stop any other state in the region from breaking its nuclear monopoly. It is also why the Israeli programme’s sole whistle-blower, Mordechai Vanunu, is a pariah 24 years after committing his “offence”. Six years on from his release to a form of loose house arrest, his hounding by the authorities – he was jailed again last month for talking to foreigners – has attracted absolutely no interest or sympathy in Israel.

If Mr Vanunu’s continuing abuse highlights Israel’s oppressive desire for Jewish power, Israelis’ self-righteousness about their navy’s attack on the Gaza flotilla reveals the flipside of this pyschosis.

The angry demonstrations sweeping the country against the world’s denunciations; the calls to revoke the citizenship of the Israeli Arab MP on board – or worse, to execute her – for treason; and the local media’s endless recycling of the soldiers’ testimonies of being “bullied” by the activists demonstrate the desperate need of Israelis to justify every injustice or atrocity while clinging to the illusion of victimhood.

The lessons imbibed from this episode – like the lessons Israelis learnt from the Goldstone report last year into the war crimes committed during Israel’s attack on Gaza, or the international criticisms of the massive firepower unleashed on Lebanon before that – are the same: that the world hates us, and that we are alone.

If the confrontation with the activists on the flotilla has proved to Israelis that the unarmed passengers were really terrorists, the world’s refusal to stay quiet has confirmed what Israelis already knew: that, deep down, non-Jews are all really anti-Semites.

Meanwhile, the lesson the rest of us need to draw from the deadly commando raid is that the world can no longer afford to indulge these delusions.

Jonathan Cook is The National’s correspondent in Nazareth and the author of Disappearing Palestine

Liberal Diaspora Jewry afraid to talk, afraid to be silent: Haaretz

in Britain, for the most part, ordinary people don’t care about the complicated story of the Middle East. They don’t buy the line that Israel stands on the front line of the war against terror.

By Linda Grant

LONDON – Last week I wrote a comment piece for the Guardian comparing the Israeli attack on the Gaza aid ships to the British assault on the Exodus in 1947. The comparison between the two events is far from exact, but both involved the running of a naval blockade as a public relations stunt, and both succeeded in dramatically winning over world opinion. In each case a more complex narrative told by the other side went unheard. Israel has failed to convince the public in Europe that those on board included terrorists smuggling arms to Hamas, and that they attacked the Israeli commandos first. As in 1947, rightly or wrongly, the sympathy was with those whose vessels were boarded, not those doing the boarding.

Here in Britain, for the most part, ordinary people don’t care about the complicated story of the Middle East. They don’t buy the line that Israel stands on the front line of the war against terror. They may know of the impoverished city of Sderot and the rocket fire it faced over time, but in the balance sheet of life and death – when, in a densely packed strip of earth blockaded from all directions, children are made to go without food, toys and medicines – human sympathy has little difficulty attaching itself to the victims.

Early on Friday morning I turned on my computer to see if my piece had run. It hadn’t. I fired off an e-mail to my editor to ask what had happened, and settled down to read Anshel Pfeffer’s June 4 column on Haaretz.com, in which he made the case that the Diaspora had failed Israel by not being the friend it needed. The close, loyal, loving friend who can tell you bluntly when you are destroying yourself.

In 2000, I published a novel about pre-state Tel Aviv, and a few years later, a nonfiction book about the months I spent observing the people on one block of Ben Yehuda Street in that same city. I define my political orientation as being on the left – the same left as authors David Grossman, Amos Oz and Etgar Keret, though not the left of historian Ilan Pappe. So Pfeffer’s piece spoke to me.

After I finished reading the column, my e-mail pinged. It was the Guardian editor. My piece had been published in the newspaper’s print edition, but was being held from the online site until after 8 A.M., when a dedicated moderator to monitor readers’ comments would become available. Since the beginning of the week, she told me, the site’s supervisors had been dealing with “appalling levels of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia and hatred.”

This is the tight place in which liberal Jews in the Diaspora find ourselves, and we can hardly breathe, let alone speak. Wanting to articulate the same critique of Israeli policy as Israeli critics, we find ourselves adding our voices to a condemnation of the Jewish state, which is turning into hate speech here. There is no evil crime of which Israel cannot be accused: It’s an outlaw state, a pariah state, a demonic force. Calls for an end to the occupation are now regarded as merely propping up Zionism, an apartheid system. The right of return is sacred; the law of return is a racist abomination.

An Indian novelist I met 18 months ago said he had been warned against me. “She’s a Zionist,” he had been told, as if I was a carrier of bubonic plague. In Europe, public opinion is tending in one direction only: An anti-Zionist narrative is being articulated in the media, and “soft” public opinion is being dragged along in its wake – especially among people who don’t know much about Israel or Palestine, but see best-selling Swedish novelists whose books are dramatized on British TV, and Irish Nobel Peace Prize winners on a mercy mission to aid a civilian population. A one-state solution, just like South Africa? Sounds lovely, they say.

Since the Spanish Civil War, the left has allied itself to a succession of progressive causes. In my lifetime these have been Czechoslovakia, Nicaragua, Northern Ireland, South Africa. They are the struggles according to which you define your politics. Today it is Palestine. In the British media, critical pro-Israel voices are drowned out by pro-Palestinian ones and the angry American Zionist right. Either you’re a supporter of apartheid or a self-hating Jew.

In such a climate, it is very difficult to speak at all. To critically support Israel is to discredit your own progressive values – to be a pariah in the artistic and intellectual communities that are your natural home. To feel you can’t stay shtum a moment longer and must express outrage is to contribute to an environment in which anti-Semites cherry-pick your words for their own abusive propaganda. To stay silent is the peaceful alternative, but for a writer the one that seems most shameful.

IDF EXECUTED MAVI MARMARA VICTIMS: Richardsilverstein

In my earlier posts about the killings aboard the Mavi Marmara, I used terms like “kill shot” and “execution-style” to describe these events. I based my judgment on the narratives told by eyewitnesses and the Turkish autopsy reports. Some readers were taken aback and accused me of overstatement, exaggeration and worse. But this video vividly confirms my strong suspicions.

It shows IDF commandos executing a passenger on the Mavi Marmara with one and possibly two point blank shots from above into the victim who lies on the boat deck. In truth, one cannot distinguish the face of the victim since it is blocked by a boat railing. But from the muzzle flashes and weapon recoils and the downward direction in which the shooter looks at his victim, it is clear this is an execution just as I described earlier.

The video caption claims this is the murder of 19 year-old Turkish-American high school student Furkan Dogan. While it is possible there is earlier footage not shown in this video that displayed the victim’s face and enabled one to identify him, I won’t vouch for Dogan as being the specific victim. But what is incontrovertible is that this is A Mavi Marmara passenger being murdered.

This changes everything. Here for the first time is evidence that the IDF was not just engaged in a defensive operation, but that it had determined to murder passengers. Gone are the hasbara rationales which defended Israel and blamed the victims for their own deaths.

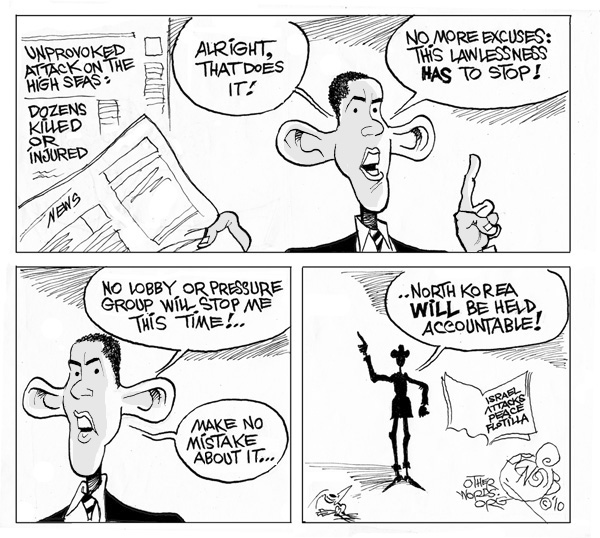

I am ashamed of Israel. I am ashamed of my president’s response to Israel.

We must get all those governments like our own who were trying to finesse this crisis, trying to put the genie back in the bottle, to stop and take stock. Sending fixers like Dan Shapiro to Israel to hondle about the the least damaging way to repair this mess simply won’t work. Shapiro is trying to figure out Israel can give up the least and gain the most. He and his boss, the president, want to figure out how Israel can ease the humanitarian crisis with a nip and a tuck–allow in more foods for example–while getting the UN to dismiss its international investigation.

The Telegraph published a similar report claiming the new Tory-led government had a deal with Israel on similar terms. The report missed a few things though. Nowhere did it say what Turkey thought about any of this. And that country, after all, is the injured party since 9 (more likely 15) of its citizens were murdered by the IDF. Do the U.S., Britain and Israel think they can work their way out of this mess without Turkey’s acquiescence?

Does Israel truly believe that its sham proposals for a two part domestic investigation will pass muster? It proposes a military panel under the leadership of an ex-general who will examine the failure without placing blame on any specific individuals. Then Netanyahu proposes a panel composed of Israeli judges to be joined by up to two foreign “observers.” This commission will not be permitted to question the actual commando killers. Which in effect renders the proceedings toothless before they even begin.

If I were Prime Minister Erdogan I’d do pretty much what he’s done so far. Put out my demands for a deal and then let everyone else scheme and manipulate in order to avoid my terms. Once they’ve exhausted themselves and come up empty, perhaps they’ll realize there is only one way to resolve the matter. Israel must apologize, pay reparations to victim’s families and all the passengers, and end the siege.

There is a simmering rage within Turkey about the way its citizens were brutalized. A Turkish-American journalist told me a poll said 60% believe their government has not done enough to express its outrage. So Israelis may express their shock at Erdogan’s obstreperousness. But they should know that behind Erdogan are 80 million very angry Turks. Is Israel prepared to face them down? And I don’t mean this only in a diplomatic sense. I mean this in a very real, tangible sense. Until now, Turks cared little for Palestine in the way that more devout Muslim nations do. Their form of Islam is fairly tolerant and laid back. That’s why they could forge an alliance with Israel for so many years. But now I can imagine Turkish shahids waging jihad on Israel. This would be an unprecedented development both for Israel and Turkey.

Obama and Abbas meet at the White House: eyeless in Gaza, Ramallah and Washington

Today, Barack Obama showed that he’s still spinning his wheels. He had Fatah’s rump West Bank president, Mahmoud Abbas to the White House for a photo-op and offered $400 million for Gaza. He offered this money to a man who has absolutely no sway in Gaza. A man who hates the government that rules Gaza and who is hated in return. Hell, Obama hates Hamas too. So what kind of charade were the two of them playing earlier today? How will this money ever get to its destination if no one will talk to the only party who can spend it?

It borders on sheer idiocy. And I say this knowing that Obama is neither an idiot not badly-intentioned. All one can say about the president’s policy is that with George Bush you knew you were getting someone who didn’t give a whit for the Palestinians and who wouldn’t lift a finger for them. With Obama, you get the illusion of a leader who cares, but who doesn’t. Or at least doesn’t care enough to do anything substantive. There are times when ineffectual leaders with good intentions can do even more damage than those like Bush who never had any good intentions to begin with.

The question is how long will Obama continue this masquerade. How long before he faces the music and comes to the realization there is only one way to do the right thing. The longer he delays the more chance there is for a deterioration in the status quo. And I’m not talking about incremental deterioration. I’m talking about catastrophic deterioration, about a situation in which Israel attacks its neighbors or is attacked in return.

Is Israel prepared for the next Gaza flotilla to be escorted by Turkish warships to its destination? Is it prepared for Turkey not just as an enemy but possibly a military enemy as well?

Today, brings distressing news of a Rasmussen survey finding that 49% of Americans blame the victims for their death on the Mavi Marmara. But when I read such a poll I always examine the questions, since subtleties of wording can lead to tipping the respondents in a certain direction. Indeed, the question asked in this poll which brought that result betrayed a “tell” as they say in poker:

Who is primarily to blame for the deadly outcome of the raid on the aid-carrying ships – Israel or the pro-Palestinian activists on the ships?

While I agree that in actuality those on the ship were “pro-Palestinian activists,” this wording helped lead to an unreliable poll result. Those three words, when suggested to the average American conjure up an unflattering image just as the phrase “pro-Israeli activist” would in a similar context (though the revulsion would be less pronounced). It would’ve been much better had the pollsters come up with a less leading, less judgmental, less emotional phrase to describe those on the Mavi Marmara. Why not just “passengers?” Or “humanitarians” or “peace activists?” Or “anti-blockade activists?”

While I dispute the wording of the question, there is no doubt that Americans have bought the hasbara campaign about this tragedy. They do not know what really happened. That’s why it’s important that video like this be seen as widely as possible. For a time, hasbara may prevail. But in the longer term the real facts and enormity of this tragedy will sink in.

In the interests of such education, I’m planning a conference here in Seattle at St. Mark’s Cathedral on Friday, June 25th on the Gaza crisis. Evergreen College Prof. Steve Niva will speak about the failure of U.S. policy in this crisis. I will speak about the current political currents inside Israel and the assault on democracy and human rights that has accompanied external attacks like the one on the Gaza flotilla. Dave Schermerhorn will speak about his experience as a Mavi Marmara survivor. We will also present a Palestinian speaker who will address the humanitarian crisis inside Gaza. So far, the conference is co-sponsored by SABEEL of the Puget Sound and the Mideast Focus Ministry. New co-sponsors will be added including Jewish and Muslim organizations.

In order to bring one speaker to Seattle, we need to raise funds for her airfare and accommodations. If you’re so moved, please click the Paypal button in my sidebar or the Donate link also in the sidebar. Your donation will defray these costs. Anything exceeding them will go to Gaza humanitarian relief.

Essay of the week: What drives Israel?: Heraldscotland

Illan Pappe, 6 Jun 2010

Probably the most bewildering aspect of the Gaza flotilla affair has been the righteous indignation expressed by the Israeli government and people.

The nature of this response is not being fully reported in the UK press, but it includes official parades celebrating the heroism of the commandos who stormed the ship and demonstrations by schoolchildren giving their unequivocal support for the government against the new wave of anti-Semitism.

As someone who was born in Israel and went enthusiastically through the socialisation and indoctrination process until my mid-20s, this reaction is all too familiar. Understanding the root of this furious defensiveness is key to comprehending the principal obstacle for peace in Israel and Palestine. One can best define this barrier as the official and popular Jewish Israeli perception of the political and cultural reality around them.

A number of factors explain this phenomenon, but three are outstanding and they are interconnected. They form the mental infrastructure on which life in Israel as a Jewish Zionist individual is based, and one from which it is almost impossible to depart – as I know too well from personal experience.

The first and most important assumption is that what used to be historical Palestine is by sacred and irrefutable right the political, cultural and religious possession of the Jewish people represented by the Zionist movement and later the state of Israel.

Most of the Israelis, politicians and citizens alike, understand that this right can’t be fully realised. But although successive governments were pragmatic enough to accept the need to enter peace negotiations and strive for some sort of territorial compromise, the dream has not been forsaken. Far more important is the conception and representation of any pragmatic policy as an act of ultimate and unprecedented international generosity.

Any Palestinian, or for that matter international, dissatisfaction with every deal offered by Israel since 1948, has therefore been seen as insulting ingratitude in the face of an accommodating and enlightened policy of the “only democracy in the Middle East”. Now, imagine that the dissatisfaction is translated into an actual, and sometimes violent, struggle and you begin to understand the righteous fury. As schoolchildren, during military service and later as adult Israeli citizens, the only explanation we received for Arab or Palestinian responses was that our civilised behaviour was being met by barbarism and antagonism of the worst kind.

According to the hegemonic narrative in Israel there are two malicious forces at work. The first is the old familiar anti-Semitic impulse of the world at large, an infectious bug that supposedly affects everyone who comes into contact with Jews. According to this narrative, the modern and civilised Jews were rejected by the Palestinians simply because they were Jews; not for instance because they stole land and water up to 1948, expelled half of Palestine’s population in 1948 and imposed a brutal occupation on the West Bank, and lately an inhuman siege on the Gaza Strip. This also explains why military action seems the only resort: since the Palestinians are seen as bent on destroying Israel through some atavistic impulse, the only conceivable way of confronting them is through military might.

The second force is also an old-new phenomenon: an Islamic civilisation bent on destroying the Jews as a faith and a nation. Mainstream Israeli orientalists, supported by new conservative academics in the United States, helped to articulate this phobia as a scholarly truth. These fears, of course, cannot be sustained unless they are constantly nourished and manipulated.

From this stems the second feature relevant to a better understanding of the Israeli Jewish society. Israel is in a state of denial. Even in 2010, with all the alternative and international means of communication and information, most of the Israeli Jews are still fed daily by media that hides from them the realities of occupation, stagnation or discrimination. This is true about the ethnic cleansing that Israel committed in 1948, which made half of Palestine’s population refugees, destroyed half the Palestinian villages and towns, and left 80% of their homeland in Israeli hands. And it’s painfully clear that even before the apartheid walls and fences were built around the occupied territories, the average Israeli did not know, and could not care, about the 40 years of systematic abuses of civil and human rights of millions of people under the direct and indirect rule of their state.

Nor have they had access to honest reports about the suffering in the Gaza Strip over the past four years. In the same way, the information they received on the flotilla fits the image of a state attacked by the combined forces of the old anti-Semitism and the new Islamic Judacidal fanatics coming to destroy the state of Israel. (After all, why would they have sent the best commando elite in the world to face defenceless human rights activists?)

As a young historian in Israel during the 1980s, it was this denial that first attracted my attention. As an aspiring professional scholar I decided to study the 1948 events and what I found in the archives sent me on a journey away from Zionism. Unconvinced by the government’s official explanation for its assault on Lebanon in 1982 and its conduct in the first Intifada in 1987, I began to realise the magnitude of the fabrication and manipulation. I could no longer subscribe to an ideology which dehumanised the native Palestinians and which propelled policies of dispossession and destruction.

The price for my intellectual dissidence was foretold: condemnation and excommunication. In 2007 I left Israel and my job at Haifa University for a teaching position in the United Kingdom, where views that in Israel would be considered at best insane, and at worst as sheer treason, are shared by almost every decent person in the country, whether or not they have any direct connection to Israel and Palestine.

That chapter in my life – too complicated to describe here – forms the basis of my forthcoming book, Out Of The Frame, to be published this autumn. But in brief, it involved the transformation of someone who had been a regular and unremarkable Israeli Zionist, and it came about because of exposure to alternative information, close relationships with several Palestinians and post-graduate studies abroad in Britain.

My quest for an authentic history of events in the Middle East required a personal de-militarisation of the mind. Even now, in 2010, Israel is in many ways a settler Prussian state: a combination of colonialist policies with a high level of militarisation in all aspects of life. This is the third feature of the Jewish state that has to be understood if one wants to comprehend the Israeli response. It is manifested in the dominance of the army over political, cultural and economic life within Israel. Defence minister Ehud Barak was the commanding officer of Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, in a military unit similar to the one that assaulted the flotilla. That background was profoundly significant in terms of the state’s Zionist response to what they and all the commando officers perceived as the most formidable and dangerous enemy.

You probably have to be born in Israel, as I was, and go through the whole process of socialisation and education – including serving in the army – to grasp the power of this militarist mentality and its dire consequences. And you need such a background to understand why the whole premise on which the international community’s approach to the Middle East is based, is utterly and disastrously wrong.

The international response is based on the assumption that more forthcoming Palestinian concessions and a continued dialogue with the Israeli political elite will produce a new reality on the ground. The official discourse in the West is that a very reasonable and attainable solution – the two states solution – is just around the corner if all sides would make one final effort. Such optimism is hopelessly misguided.

The only version of this solution that is acceptable to Israel is the one that both the tamed Palestine Authority in Ramallah and the more assertive Hamas in Gaza could never accept. It is an offer to imprison the Palestinians in stateless enclaves in return for ending their struggle. And thus even before one discusses either an alternative solution – one democratic state for all, which I myself support – or explores a more plausible two-states settlement, one has to transform fundamentally the Israeli official and public mindset. It is this mentality which is the principal barrier to a peaceful reconciliation within the fractured terrain of Israel and Palestine.

How can one change it? That is the biggest challenge for activists within Palestine and Israel, for Palestinians and their supporters abroad and for anyone in the world who cares about peace in the Middle East. What is needed is, firstly, recognition that the analysis put forward here is valid and acceptable. Only then can one discuss the prognosis.

It is difficult to expect people to revisit a history of more than 60 years in order to comprehend better why the present international agenda on Israel and Palestine is misguided and harmful. But one can surely expect politicians, political strategists and journalists to reappraise what has been euphemistically called the “peace process” ever since 1948. They need also to be reminded that what actually happened.

Since 1948, Palestinians have been struggling against the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. During that year, they lost 80% of their homeland and half of them were expelled. In 1967, they lost the remaining 20%. They were fragmented geographically and traumatised like no other people during the second half of the 20th century. And had it not been for the steadfastness of their national movement, the fragmentation would have enabled Israel to take over historical Palestine as a whole and push the Palestinians into oblivion.

Transforming a mindset is a long process of education and enlightenment. Against all the odds, some alternative groups within Israel have begun this long and winding road to salvation. But in the meantime Israeli policies, such as the blockade on Gaza, have to be stopped. They will not cease in response to feeble condemnations of the kind we heard last week, nor is the movement inside Israel strong enough to produce a change in the foreseeable future. The danger is not only the continued destruction of the Palestinians but a constant Israeli brinkmanship that could lead to a regional war, with dire consequences for the stability of the world as a whole.

In the past, the free world faced dangerous situations like that by taking firm actions such as the sanctions against South Africa and Serbia. Only sustained and serious pressure by Western governments on Israel will drive the message home that the strategy of force and the policy of oppression are not accepted morally or politically by the world to which Israel wants to belong.

The continued diplomacy of negotiations and “peace talks” enables the Israelis to pursue uninterruptedly the same strategies, and the longer this continues, the more difficult it will be to undo them. Now is the time to unite with the Arab and Muslim worlds in offering Israel a ticket to normality and acceptance in return for an unconditional departure from past ideologies and practices.

Removing the army from the lives of the oppressed Palestinians in the West Bank, lifting the blockade in Gaza and stopping the racist and discriminatory legislation against the Palestinians inside Israel, could be welcome steps towards peace.

It is also vital to discuss seriously and without ethnic prejudices the return of the Palestinian refugees in a way that would respect their basic right of repatriation and the chances for reconciliation in Israel and Palestine. Any political outfit that could promise these achievements should be endorsed, welcomed and implemented by the international community and the people who live between the river Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea.

And then the only flotillas making their way to Gaza would be those of tourists and pilgrims.

Ilan Pappe is professor of history at the University of Exeter, and director of the European Centre for Palestine Studies. His books include The Ethnic Cleansing Of Palestine and A History Of Modern Palestine. His forthcoming memoir, Out Of The Frame (published this October by Pluto Press), will chart his break with mainstream Israeli scholarship and its consequences.