EDITOR: Listen to the message of Israelis on the Nakba

For those good souls, who forever hope for a solution brought about by the non-existing left in Israel, an important object lesson is listening to common Israelis in the street. The combination of racism, arrogance, total lack of knowledge as well as of a lack of shame, has to be seen to be believed. Apart from denying any responsibility for the Nakba, they normally combine this sentiment with a wish to repeat it, and get every Palestinian out of their native land. Those colonials are not for turning, and those who put their hope in their transformation, may as well wait for the messiah, as he is likely to come earlier than such an impossible transformation.

Speaking to Israelis on the Nakba: The Real News

Every year on May 15, Palestinians the world over mourn what is known as Nakba Day. The Nakba is Arabic of catastrophe and represents the 1948 ethnic cleansing when nearly 800,000 Palestinians became refugees. In this segment, Lia Tarachansky of The Real News and Yossef(a) Mekyton of Zochrot speak to Israelis about what they know of this history and the war of 1948, the result of which was the establishment of the state of Israel.

Mubarak: Terror to spread if Israel continues stalling peace talks: Haaretz

Saeb Erekat says Abbas-Mitchell meeting that the PA hopes to achieve a two-state solution within 4 months.

Terrorism will spread if Israel fails to address “fundamental” issues with the Palestinians, Egyptian President Hosny Mubarak warned on Wednesday during talks with Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

Mubarak criticised Israel’s refusal to address the definitive borders of a future Palestinian state during indirect peace talks with the Palestinians that have been approved by Arab nations.

According to the Egyptian president, Israel’s insistence on discussing only “secondary issues,” such as the environment and the rights to airspace, threatened to stall any peaceful resolution of the conflict.

“Then we will see terrorism increase and spread throughout the world,” Mubarak said.

Berlusconi said Italy, together with its international allies, is “putting pressure” on both the Israelis and Palestinians to resume negotiations.

Earlier Wednesday, top Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat said that U.S. President Barack Obama’s Middle East envoy George Mitchell and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas discussed possible outlines of a future Palestinian state during their Ramallah meeting.

“We are focusing on final-status issues like borders and security,” Saeb Erekat told reporters after the meeting between Abbas and Mitchell, who is mediating indirect peace talks between Israel and the Palestinians.

“We hope that in the next four months we can achieve the two-state solution on the 1967 borders,” said Erekat, reiterating a Palestinian demand that Israel withdraws from Palestinian territory it captured in the 1967 Middle East war.

Mitchell will shuttle between Israel and the West Bank for the second substantive sessions since the Palestinians agreed to the indirect “proximity” talks, which have been given a maximum of four months to produce results.

Israeli leaders have said the Palestinians can raise core issues like the status of Jerusalem, final borders and the issue of Palestinian refugees in the indirect talks, but only direct negotiations can resolve them.

Palestinians say they could hold direct talks if Israel halts all settlement activities on occupied land.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said this week his government “is prepared to do things that are not simple, that are difficult”.

Government sources said Netanyahu is favorably examining a proposal to expropriate land from Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank to build a road between Ramallah and a new Palestinian town under construction.

Abbas broke with tradition on Monday by failing to give a speech on the day that Palestinians mourn the creation of Israel, which they call the “nakba”, or catastrophe. Analysts said he wanted to avoid an occasion in which he would be expected to condemn Israel in strong language.

The White House has said it will hold either side accountable for any action that could undermine negotiations.

The pledge appeared in part aimed at satisfying Abbas’ fears that Israel’s right-leaning government might announce further expansion of Jewish housing in and around Jerusalem.

Obama also urged Abbas to do all he can to prevent acts of incitement or delegitimization of Israel.

Israel captured East Jerusalem along with the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967, and considers all of Jerusalem its capital, a claim that is not recognized internationally.

Palestinians want East Jerusalem as the capital of the state they intend to establish in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Direct peace talks were suspended in late 2008.

EDITOR: The Pressures Start in Earnest

We all knew that the Jewish Lobby, both in AIPAC and beyond it, will start putting pressure on Obama in good time for the elections in November. Obama cannot afford to avoid them, and they will be as insistent as anything, trying hard to defend the indefensible positions of Israel. That is their job, or at least, that is how they see it. Obama is in for a grueling time, to put it mildly.

U.S. Jewish lawmakers urge Obama to visit Israel: Haaretz

Three dozen Jewish Democratic lawmakers met with Obama for an hour on Tuesday night.

Jewish members of Congress urged President Barack Obama in a meeting Tuesday night to discuss his commitment to Israel publicly and travel to the country to demonstrate his support, participants said.

Obama convened the 1-hour meeting with three dozen Jewish Democratic lawmakers, the first such gathering of his presidency, after some members of Congress raised concerns about his administration’s attitudes and positions on Israel, said Rep. Shelley Berkley, one lawmaker present.

The meeting came at a delicate time, with U.S.-brokered peace talks between Israel and the Palestinians getting under way. It also follows a diplomatic spat between the United States and Israel in March that occurred when construction plans in contested east Jerusalem were announced in the middle of a visit to Israel by Vice President Joe Biden.

The Obama administration strongly rebuked Israel over the incident, but some, particularly conservatives, criticized the U.S. reaction as too strong and unfair to Israel.

“It was agreed that both the Israelis and the U.S. government probably could have handled that situation a little better,” Rep. Steve Rothman, said after Tuesday night’s meeting, while asserting that from a military and intelligence-sharing perspective, the Obama administration is the best U.S. administration ever for Israel.

He said administration critics were trying to distort that, and Obama and his Jewish supporters in Congress needed to set the record straight.

Berkley, however, said that while she believed the president thought he was doing what was right for Israel and the United States, misgivings remained for those steeped in the issue and highly sensitive to nuances.

“I do want to see the president step up and vocalize his support for Israel far more than he has. He just needs to do that,” Berkley said.

Obama supports a two-state solution for Israel and the Palestinians. Berkley said most lawmakers in the meeting did too, but not at the expense of Israel’s security, and it could not be a U.S.-imposed peace.

Berkley said Obama assured the group he had no intention of imposing an American plan on the two parties.

Obama last visited Israel during his presidential campaign.

I’d say he’s changed all right: The Guardian CiF

Peter Beinart has written a devastating piece on American Jewish leadership for the New York Review of Books.

Michael Tomasky

That sentence was probably fairly ho-hum to you. But if you know either Beinart, or American Jewish leadership, or the New York Review, you know that it was in fact a rather remarkable collection of facts.

Beinart is a former editor of The New Republic magazine and was, in the run-up-to-Iraq days, a highly vocal liberal hawk, casting about at anti-war liberals in pretty direct ways. TNR has always been a liberal magazine domestically but a sometimes pretty conservative one on foreign policy, especially on anything pertaining to Israel. American Jewish leadership has not heretofore been a target of Beinart’s in the 15 or more years he’s been at this. And the New York Review, for which I write and which I think is America’s greatest magazine, is known for a generally quite critical posture toward the Israeli occupation.

Put it all together, it’s an astonishing combination.

Beinart’s main point for me is that US Jewish leadership, by adopting a policy of supporting Israel at all costs, no matter what the government, no matter what it does, has completely lost faith with a bedrock principle upon which Israel was founded, more on which below. Also, that it is badly serving its own cause and Israel’s and has lost touch with younger American Jews, who care about Israel far less than this older generation does. Finally (I guess there were several main points), that Israel’s hard line has made the question of Palestinian suffering one that Jews in Israel and the US needn’t even bother thinking about. Beinart:

In 2004, in an effort to prevent weapons smuggling from Egypt, Israeli tanks and bulldozers demolished hundreds of houses in the Rafah refugee camp in the southern Gaza Strip. Watching television, a veteran Israeli commentator and politician named Tommy Lapid saw an elderly Palestinian woman crouched on all fours looking for her medicines amid the ruins of her home. He said she reminded him of his grandmother.

In that moment, Lapid captured the spirit that is suffocating within organized American Jewish life. To begin with, he watched. In my experience, there is an epidemic of not watching among American Zionists today. A Red Cross study on malnutrition in the Gaza Strip, a bill in the Knesset to allow Jewish neighborhoods to bar entry to Israeli Arabs, an Israeli human rights report on settlers burning Palestinian olive groves, three more Palestinian teenagers shot—it’s unpleasant. Rationalizing and minimizing Palestinian suffering has become a kind of game. In a more recent report on how to foster Zionism among America’s young, Luntz urges American Jewish groups to use the word “Arabs, not Palestinians,” since “the term ‘Palestinians’ evokes images of refugee camps, victims and oppression,” while “‘Arab’ says wealth, oil and Islam.”

Of course, Israel—like the United States—must sometimes take morally difficult actions in its own defense. But they are morally difficult only if you allow yourself some human connection to the other side. Otherwise, security justifies everything. The heads of AIPAC and the Presidents’ Conference should ask themselves what Israel’s leaders would have to do or say to make them scream “no.” After all, Lieberman is foreign minister; Effi Eitam is touring American universities; settlements are growing at triple the rate of the Israeli population; half of Israeli Jewish high school students want Arabs barred from the Knesset. If the line has not yet been crossed, where is the line?

What infuriated critics about Lapid’s comment was that his grandmother died at Auschwitz. How dare he defile the memory of the Holocaust? Of course, the Holocaust is immeasurably worse than anything Israel has done or ever will do. But at least Lapid used Jewish suffering to connect to the suffering of others. In the world of AIPAC, the Holocaust analogies never stop, and their message is always the same: Jews are licensed by their victimhood to worry only about themselves. Many of Israel’s founders believed that with statehood, Jews would rightly be judged on the way they treated the non-Jews living under their dominion. “For the first time we shall be the majority living with a minority,” Knesset member Pinchas Lavon declared in 1948, “and we shall be called upon to provide an example and prove how Jews live with a minority.”

But the message of the American Jewish establishment and its allies in the Netanyahu government is exactly the opposite: since Jews are history’s permanent victims, always on the knife-edge of extinction, moral responsibility is a luxury Israel does not have. Its only responsibility is to survive. As former Knesset speaker Avraham Burg writes in his remarkable 2008 book, The Holocaust Is Over; We Must Rise From Its Ashes, “Victimhood sets you free.”

This obsession with victimhood lies at the heart of why Zionism is dying among America’s secular Jewish young. It simply bears no relationship to their lived experience, or what they have seen of Israel’s. Yes, Israel faces threats from Hezbollah and Hamas. Yes, Israelis understandably worry about a nuclear Iran. But the dilemmas you face when you possess dozens or hundreds of nuclear weapons, and your adversary, however despicable, may acquire one, are not the dilemmas of the Warsaw Ghetto. The year 2010 is not, as Benjamin Netanyahu has claimed, 1938. The drama of Jewish victimhood—a drama that feels natural to many Jews who lived through 1938, 1948, or even 1967—strikes most of today’s young American Jews as farce.

But there is a different Zionist calling, which has never been more desperately relevant. It has its roots in Israel’s Independence Proclamation, which promised that the Jewish state “will be based on the precepts of liberty, justice and peace taught by the Hebrew prophets,” and in the December 1948 letter from Albert Einstein, Hannah Arendt, and others to The New York Times, protesting right-wing Zionist leader Menachem Begin’s visit to the United States after his party’s militias massacred Arab civilians in the village of Deir Yassin. It is a call to recognize that in a world in which Jewish fortunes have radically changed, the best way to memorialize the history of Jewish suffering is through the ethical use of Jewish power.

It’s pretty eye-popping stuff, coming from Peter. It’s completely impossible for American Jewish leaders to paint him as unsympathetic. Some will try of course, but it just isn’t credible.

I recommend also this interview Beinart gave yesterday to the Tablet, an online Jewish-interest journal. They ask:

Have your politics shifted over time? In 2004, under your leadership, The New Republic endorsed Joe Lieberman for president. I don’t think he would agree with your essay.

Yeah, I think I have shifted, not only on this issue. Anyone who reads my new book will clearly see a shift. But I also didn’t really write about this issue very much at The New Republic. I do think I’ve shifted, and it’s partly personal things, and also I didn’t envision that you were going to have a government of Shas, Avigdor Lieberman, and Benjamin Netanyahu.

I’ll say he’s shifted. I know: I crossed swords in public with Peter over the war. He was so sure of himself then. But here is a rare and admirable example of someone who has rethought something pretty fundamental. This essay has the potential to start a conversation that could lead Aipac and other outfits like it to shift their Israel right-or-wrong thinking.

Palestinians mark ‘Nakba’ with tears and questions: BBC

By Paul Wood

BBC News, Jerusalem

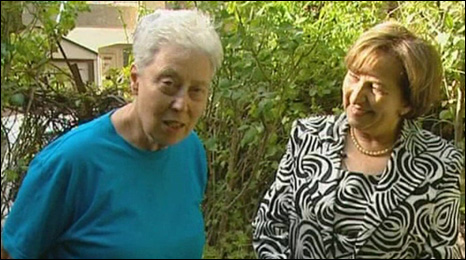

Claudette Habesch stood at the gate of what had once been her family house, tears in her eyes as she pointed to the garden shaded by a large date palm.

“It was beautiful, a lot of fun, a lot of happiness,” she said, recalling an Arab childhood spent in Jerusalem before her family fled in 1948.

“(Then) there was the foundation of the state of Israel – on my own homeland, on my own home.”

About half of something like 750,000 Arabs left and about half were expelled – so in a way both narratives are right

Tom Segev

Historian

As a little girl, she often used to wonder “who is sleeping in my bed, who is playing with my dog?”

For Jewish Israelis, 1948 is celebrated as the year their war for independence was brought to a successful conclusion.

For Arabs, Israel’s birth meant the “Nakba” or “catastrophe” when about 700,000 Palestinians were displaced and dispossessed – which is being marked and remebered this week.

“We had two bombs here in the back garden,” says Mrs Habesch. “My father had to take us out for our physical security.

“We did not go out of here willingly and we were not able to come back.”

‘Both right’

The Israeli narrative of 1948 says the Palestinians left of their own accord; the Arab narrative says they were forced out.

Key background: Refugees

The Israeli historian Tom Segev says the truth is somewhere in between.

“About half of something like 750,000 Arabs left and about half were expelled – so in a way both narratives are right,” he told me.

“The basic dream of the Zionist movement was to have maximum land with minimum population,” he went on.

“When the war broke out it was obvious to everybody, whoever wins would expel parts of the population. That was because 1948 was not the beginning of the conflict.”

Rights

Looking around her former garden, Mrs Habesch bumped into her childhood friend, Ruthie, a Jewish woman.

She still lives in a small house in the grounds which her parents had first rented from Mrs Habesch’s family before 1948.

The two women, both now in their 60s, swapped stories of hiding among the dahlias while male visitors to the house smoked nargila (water-pipe) outside.

“She has the right to live here. I don’t grudge her this,” said Mrs Habesch as we left.

“I don’t want to throw anyone out on the streets but I have to have people recognise the right to my property.”

There were more tears as she declared: “This is my home – and I go out as a stranger. Why? I need someone to explain to me.”

Returns

Mrs Habesch says she is going to court to establish ownership – not that she has much chance of success.

The 1948 refugees and their descendants are now said to total some 4.7 million people.

The Israelis says that if all were allowed to come back it would mean the end of their country as a Jewish state.

That is why the “right of return” is one of the seemingly insoluble issues of the peace process.

Under any future peace deal, Israel might allow a symbolic number of “family reunifications”, probably just a few thousand.

So with or without a peace agreement, very few of those who left in 1948 and their descendants will be back to claim their property.

Elvis Costello pulls out of ‘political’ gigs: The Indepoendent

By Donald Macintyre in Jerusalem

Wednesday, 19 May 2010

Elvis Costello has become one of the biggest names in music to join a cultural boycott of Israel by cancelling two planned concerts there at the end of next month.

The British singer-songwriter announced on his website that he was pulling out of two dates in Caesarea on 30 June and 1 July, saying: “Merely having your name added to a concert may be interpreted as a political act… and it may be assumed that one has no mind for the suffering of the innocent.”

In a highly personal statement, Costello said he was conscious that many of those who would have come to hear him “question the policies of their government on settlement and deplore conditions that visit intimidation, humiliation or much worse on Palestinian civilians in the name of national security”.

At the same time he said – in what appeared to be an oblique reference to suicide and other attacks on Israeli civilians – that he was “keenly aware of the sensitivity of these themes in the wake of so many despicable acts of violence perpetrated in the name of liberation”. But he added: “Sometimes a silence in music is better than adding to the static.”

Costello’s decision follows an earlier concert cancellation this year by guitarist Carlos Santana but contrasts with those of Paul McCartney in 2008 and Leonard Cohen last year, both of whom played dates in Israel. McCartney made a point of visiting the West Bank during his trip, while Cohen offered to play in Ramallah and donated the proceeds of his Tel Aviv gig to co-existence projects.

Challenging Canada’s myths about its role in Palestine: The Electronic Intifada

Sean F. McMahon,18 May 2010

At the end of March, the Liberal Party of Canada staged a conference exploring the challenges Canada will face in 2017, the state’s 150th birthday. Robert Fowler, Canada’s longest-serving ambassador to the United Nations and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s former special envoy to Niger, caused a fervor on the final day of the conference by contending that Canada’s reputation and foreign policy effectiveness in the Middle East have been diminished as a result of domestic pandering to Jewish voters — because foreign policy has been put in the service of domestic electoral concerns.

Fowler’s comments have been read as critical by the corporate media, a reading sure to be reinforced by Liberal Party leader Michael Ignatieff’s rejection of them and the predictable responses that followed from Israeli apologists. This is a perfunctory reading. Fowler’s comments are hardly remarkable for their muted critique. Instead, they are notable for their larger political function — for the manner in which they mythologize Canadian policy to the Middle East.

Fowler is not alone in claiming that Canada has a reputation for being fair, just and objective as regards the Middle East. He is, in fact, only one of many reproducing this fantasy. Canada’s policy has always been markedly tilted toward Israel in a way that has compromised Palestinian rights and damaged prospects for peace and justice.

Fowler’s substantive remarks began with the observation that Canada has turned inward and its “reputation and proud international tradition have been diminished as a result.” From this global observation, he moved to a regional focus and the challenges the Middle East poses, and put forward several rhetorical questions:

“Where is the measure which for so long characterized Canada’s policy toward [the Middle East]? Before, that is, Canada’s politicians began using foreign policy exclusively for domestic purposes; before the scramble to lock up the Jewish vote in Canada meant selling out our widely-admired and long-established reputation for fairness and justice in this most volatile and dangerous region of the world?”

Fowler followed these questions with the pointed statement: “I … deplore the abandonment of our hard-won reputation for objective analysis and decency as a result of our reckless Middle Eastern posturing.” Finally, he noted that Canadian support of policies that make Palestinian-Israeli peace more remote “did not begin with our present government, even if the extent to which radical voices within domestic constituencies are indulged has, over the past few years, been taken to a whole new level” (Video of Fowler’s presentation).

Fowler’s comparison suggests a “before” and “after” period in the Canadian approach to the issue. Sometime in the past, and he is imprecise as regards the exact timing, Canadian foreign policy to the Middle East shifted decisively in Israel’s favor. The second part of his comparison is correct — contemporary Canadian policy is uncritically supportive of Israel. However, the first part of his comparison is ideological fantasy. Canadian policy to the Middle East, and particularly Palestine, was never measured, fair or just. Canadian policy has not even been decent. As for Canada’s reputation, it is just that — Canada’s.

Recent Canadian policy vis-a-vis Israel and the Palestinians has been uncritically supportive of the former. Early last year, as a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council Canada was the only state to vote against a motion condemning Israel’s January 2009 massacre in the Gaza Strip. Then, Canada tried to block the UN nuclear assembly from passing a resolution calling “for Israel to open its nuclear facilities to UN inspection and sign up to the non-proliferation treaty” and dismissed the findings of the UN-commissioned Goldstone report.

Canadian support for Israel is nothing new. In fact, supporting Israel and denying Palestinian rights has been persistent Canadian policy. In 1947, Canada supported the creation of the State of Israel through the UN partition of Palestine, and in 1948 was one of the first states to recognize Israel.

While Canada condemned the 1956 British-French-Israeli invasion of Egypt and established the first UN peacekeeping force (a period Fowler lauded), during the War of 1967 Canada supported Israel, the aggressor. According to scholar Paul Noble, Canadian policy in the 1970s refused to recognize Palestinian national rights, including the right to self-determination (Canada and the Arab World, University of Alberta Press, 1985, p.102).

Tareq Ismael similarly notes that in the 1980s, Canada voted against UN resolutions “calling for sanctions against Israel’s annexation of the occupied Syrian Golan Heights” and urging “all governments to recognize the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people,” (Canada and the Arab World, University of Alberta Press, 1985, p.19).

In the 1990s Canada joined the international consensus supporting the Oslo process. The Oslo process effectively ended in 2000 and by 2003 Canada opposed the International Court of Justice (ICJ) examining the issue of Israel’s apartheid wall in the occupied West Bank and Jerusalem. And since the ICJ issued its advisory opinion on Israel’s wall in the West Bank in 2004, Canada, in violation of the opinion, has not pressured Israel to dismantle the wall.

Serious scholars of Canadian foreign policy offer the same characterization: Canada has always been pro-Israel. The assessment Peyton Lyon offered in International Perspectives in the 1980s is as accurate now as it was then (presumably during Fowler’s “measured” period and before his “shift” in Canadian policy towards Israel): “Canada’s approach [to the Middle East] has in fact long tilted in favor of Israel,” and “[o]utside observers have always categorized Canada as one of Israel’s most predictable supporters” (“Canada’s Middle East Tilt,” p. 3). Of course, this Canadian support denied Palestinians their rights and the causes of justice and peace.

National mythologies are not built on single utterances, but rather repeated statements. Like Fowler, former Minister of Foreign Affairs Bill Graham and former Canadian ambassador to the UN, Paul Heinbecker, recently invoked and reproduced the same Canadian mythology. During Israel’s 2006 attack on Lebanon, Graham lamented the current government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper for its “abandonment of Canada’s historic role as a bridge-builder.” He reminded the reader that it “is vital for middle-power nations such as Canada to pursue a fair-minded and balanced foreign policy” lest Canada, in particular, lose its “ability to act as peacekeeper and honest broker internationally” (“Bill Graham on the Middle East,” Globe and Mail, 2 August 2006).

In 2009, after Canada voted against the UN Human Rights Council motion condemning Israel for its massacre of Palestinians in Gaza, Heinbecker said that while “always considered ‘a friend of Israel,’ until recently Ottawa’s representatives at the UN voted on Middle East issues on the basis of ‘principle’ and ‘fair-mindedness'” (Bruce Campion-Smith and Les Whittington, “Canada votes alone for Israel,” Toronto Star, 13 January 2009).

Canada has long purported to be balanced, objective and neutral in its foreign policy to the Middle East. This claim is baseless, and exclusively Canadian; no one other than Canadians recognizes Canadian policy as anything less than resolutely partisan towards Israel. Worse yet, it is deleterious to the causes of peace and justice in the region. Canadians desirous to serve these causes must stop reproducing this made in Canada myth. The first step towards reconciliation and peace in Palestine must involve an honest historical accounting, particularly of the events of the 1947-1948 ethnic cleansing. For Canadian foreign policy to make any positive contributions to these ends, its history must be similarly appraised, not ideologically valorized.

Sean F. McMahon is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the American University in Cairo and author of The Discourse of Palestinian-Israeli Relations. He can be reached at: smcmahon A T aucegypt D O T edu.

PA boycott campaign gains momentum: YNet

Palestinian governors urge citizens to cooperate with settlement product ban; activists distribute pamphlets listing banned items. ‘We can manage this economic system,’ says Palestinian-appointed Jerusalem governor

Ali Waked

Published: 05.18.10, 15:19 / Israel News

Hundreds of activists took to the streets of the West Bank on Tuesday and distributed brochures calling on the Palestinians to boycott settlement products.

The Palestinian Authority held a press conferences, briefings and ceremonies in which the local governors urged the public to cooperate with “you and your conscience” campaign – that is meant to reach every single household.

Closed Market

Yesha Council responds to new Palestinian campaign distributing list of banned Israeli companies, calls for ‘immediate response’. Prime Minister Netanyahu urged to refuse to take part in proximity talks

Click here for full list of banned products

Bethlehem Governor Abdul Fattah Hamayel said the campaign was a breakthrough in the Palestinian struggle, as part of “the open war against the occupation.

“Our goal is to cut off the settlements that harm us and steal our resources on a daily basis,” he said.

Boycott taken a step further in West Bank’s Salfit village (Photo: AP)

Nablus governor Jibreen al-Bakri said the boycott has led to the closure of 17 factories in the settlements thus far, and called on the Palestinian public – and especially the merchants – to honor the new law.

Palestinian activists were hopeful the campaign would lead to mass mobilization of the public, and help weaken the settlements, which will contribute to the success of negotiations. Most Palestinians view the settlements as the major impediment to a political arrangement with Israel.

The boycott campaign also reached the capital, and Palestinian-appointed governor of Jerusalem Adnan al-Husseini said it was important because it emphasizes the exploitation that the Palestinians are subjected to.

Speaking at a press conference in north-east of Jerusalem, al-Husseini said, “I call all the citizens worldwide to boycott the settlement products deemed illegal by the world. We can manage this economic system,” he said.

The press conference was also attended by the mufti of the Palestinian Authority and senior Palestinian officials in the Jerusalem area.

EDITOR: A macabre Sense of Humour – The Museum of Intolerance

You have to read this to believe it, and even then it is difficult. What will come next? The Museum Of Independence in Jaffa? The Museum of Brotherly Love in Dir Yasin? The Nakba Hotel in Tantura?

Museum of Tolerance Special Report / Part I: Holes, Holiness and Hollywood: Haaretz

On the connection between the California-based Simon Wiesenthal Center, run by one of America’s most famous rabbis, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and a feverish excavation at what is probably Israel’s most secret civilian building site.

By Nir Hasson

‘Removal of nuisances’

Sometimes a lack of sensitivity or even an innocent mistake exposes a major truth. On the Web site of Moriah, a public company for infrastructure work that belongs to the Jerusalem municipality, one can find descriptions of various projects in which the company is involved. Among them is the Museum of Tolerance: “The Simon Wiesenthal Center, the entrepreneur for the construction of the Museum of Tolerance in central Jerusalem, asked Moriah to carry out preparatory and infrastructure work for the project,” says the site. Immediately afterward, under the heading “Objective,” it says: “Carrying out infrastructure work, removal of nuisances in the area of the project …” What the site calls “nuisances” are in fact skeletons, bones and skulls. Hundreds of skeletons that were buried in Jerusalem’s central Muslim cemetery over a period of some 1,000 years.

A Haaretz investigation indicates that the “nuisances” were cleared away from the site swiftly and clandestinely during five grueling months of nonstop work. Testimonies of participants who worked at the site, which were obtained by Haaretz, indicate that the skeletons were removed as quickly as possible to enable the start of construction on the museum. “That wasn’t archaeology, it was contract work,” claimed one of the workers.

The story of the Museum of Tolerance is one of a clash between worlds, between the concealed subterranean world of dead bodies − members of the Muslim community who were buried in the soil of Jerusalem − and an American Jewish institution in Los Angeles with Hollywood-style panache, the Simon Wiesenthal Center. The institution is headed by Marvin Hier, an American Jew who has an open door to U.S. presidents, and the man who brought California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to Israel for the museum’s groundbreaking ceremony in 2004. Opposing him is the leader of the northern branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel, who has tried to block the project, it has been claimed, out of cynical and political motives.

The High Court of Justice was also involved in the story, with several petitions placed on its desk in an effort to prevent the realization of the ambitious and controversial project. The permission finally granted by the High Court to go forward was based on a controversial opinion submitted to it by the Antiquities Authority, and on the fact that the project was supposed to be designed by preeminent architect Frank Gehry, who has since withdrawn from the assignment. Also involved in the affair are two prominent former members of the Jerusalem municipality, who are currently suspected of criminal offenses in other real estate projects: former prime minister Ehud Olmert, who was mayor of Jerusalem, and former municipal engineer Uri Sheetrit.

Also involved in the story are Tel Aviv University and an archaeologist who works for the university, Alon Shavit. Shavit is a key figure in this story, who has held many jobs related to moving the graves located beneath the land on which the museum is slated to be built. Among other things, he was the expert responsible for the removal work and the contractor in charge of carrying it out, and the company he established paid the excavators’ salaries.

There are also arguments among archaeologists. Now all that is left in the long and complex unfolding of events is a large lot with a huge open pit, in the heart of the city of Jerusalem.

To this day, for most Jerusalemites, the Museum of Tolerance is the six-meter-high metal fence that surrounds a construction site that has been off-limits for the past six years. Unlike most other building sites − here it is difficult, if not impossible, to find a slit through which to peek inside. Along the top of the fence are security cameras and spotlights; parts of it are edged with barbed wire. During the months of excavation the site was probably the most secret civilian construction site in Israel. Today it is quite deserted. But if we could go back to the period from about November 2008 to April 2009, we would see a place bustling with hundreds of workers employed in the excavations in three shifts around the clock.

The five months of excavation are documented in a series of exclusive pictures that are published here for the first time. In one picture a worn cardboard box takes up most of the photograph. Someone drew a schematic bone on the box as in a child’s drawing and wrote “scattered items,” and afterward erased the words. Other words are also erased. The number L4316 marks the “locus” − a sequential serial number in archaeological jargon. The box is far too small to contain the bones that stick out from both sides; the cover doesn’t close and is torn.

Another photograph depicts an ancient skull that was apparently exposed to the light hundreds of years after its owner was buried in the Jerusalem soil. In the area of the crown one can see new fractures, perhaps from an imprecise blow from a hoe. Above it there is still a large rock, and to its right a cardboard box. In the top half of the picture one can sees it is broad daylight and young Israelis, the excavators, are engaged in their work. Anyone who so wishes can perhaps find in the hollow eyes of the skull a look of amazement at what it is seeing.

In the past two weeks, in the open parts of the site that still constitute a cemetery, workers have suddenly begun to show up among the graves: As with a huge puzzle, the workers are reassembling the tombstones and more or less restoring the graves. The workers are emissaries, not of the government, but of the northern branch of Israel’s Islamic Movement.

Mohammed’s companions

The Ma’am Allah cemetery (the name would eventually be distorted to “Mamilla” and expanded in meaning to describe the entire area) originated in medieval Jerusalem, at the start of the last millennium. Burial at the site continued until the early 20th century. Muslim tradition has it that Prophet Mohammed’s companions were also buried here. Another tradition mentions the burial of 70,000 of Saladin’s soldiers in the same place. At its peak the cemetery covered an area of about 200 dunams (some 50 acres), so that in effect today large parts of downtown Jerusalem are built over graves.

According to estimates, the cemetery included most of Independence Park, the Experimental School, Agron Street, Beit Agron, Kikar Hahatulot (Cats’ Square) and other areas. The change in the situation of the cemetery began with the process by which Jerusalem expanded outside the walls of the Old City, in the mid-19th century: By then it was no longer in a distant, peripheral area, but rather in the heart of a growing, modern city. That was also the start of tensions between respect for the dead and tradition on the one hand, and the value of the land, which was worth its weight in gold, on the other. Like many other Muslim cemeteries in Israel, this one was also neglected for many decades, and today is overgrown with weeds and full of broken tombstones.

It is hard to think of anything further from the old and crumbling cemetery than the life of Rabbi Marvin Hier, the founder and director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, and one of the most important and influential rabbis in the United States. A series of pictures of Hier afford us a small glimpse into his world; among the pictures he is seen in the company of two presidents, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton; one pope, John Paul II; and a large number of actors: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Will Smith, Whoopi Goldberg, Ben Kingsley and others.

The first Museum of Tolerance that was built by Hier, and opened in 1993 in Los Angeles, became amazingly successful, with a quarter of a million visitors a year who come to view the exhibits and to participate in the interactive displays in which the museum specializes. One of Hier’s great achievements was the passage of a law in the state requiring students and members of the security forces in California to visit his museum.

That same year, toward the end of Teddy Kollek’s final term as mayor of Jerusalem, the idea of building a Jerusalem branch of the Museum of Tolerance − a “Center for Human Dignity − Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem,” by its full name − was considered. The concept was promoted enthusiastically during the tenure of Kollek’s successor, Ehud Olmert. “A glorious project that in addition to its cultural and educational objective will also constitute a work of art in itself and a site that will attract tourists to Jerusalem and contribute to the tourism industry in Israel as well …” − thus the museum is described in the Wiesenthal Center’s reply, submitted to the High Court, to the Islamic Movement’s petition for a ban on work at the site.

The initiators of the project say it was Kollek who first suggested creating a Museum of Tolerance in his city, after a visit to the original institution in Los Angeles. Kollek’s associate Ruth Cheshin, president of the Jerusalem Foundation, which the late mayor founded, remembers things differently: “He was in favor of a museum of tolerance, but didn’t like the idea proposed by the Wiesenthal Center. He said that this was not Los Angeles, and a museum for tolerance should grow out of the place rather than being ‘imported.’”

Kollek’s successor, Olmert, was also opposed to the idea at first. Also among the opponents were Yad Vashem in Jerusalem and the Diaspora Museum in Tel Aviv, which feared the competition.

“Building the museum is unnecessary. It is totally unacceptable and irregular for the government to put land at the disposal of foreign citizens who do not represent any group among the Jewish people,” said the spokeswoman of Yad Vashem at the time, Iris Rosenberg.

As a result of the pressure, the initiators of the museum promised not to deal with the Holocaust, and Yad Vashem removed its opposition, as did Olmert, who subsequently became an enthusiastic supporter of the museum.

Mayor Olmert designated the site for the Museum of Tolerance, and later, as minister of Indutry and Trade, in charge of the Israel Lands Authority, he signed the agreement awarding the Wiesenthal Center the site.

The paths of the Wiesenthal Center and Ehud Olmert also cross in the indictment now being deliberated on in the Jerusalem District Court in the so-called “Rishontours” case. According to the charges, at the end of April 2003, Olmert traveled to Paris and New York, with his expenses being covered by three organizations. One of them was the Wiesenthal Center, which paid $5,765 for the trip. Hier’s son Abe is one of the witnesses for the prosecution. Two Olmert associates − his attorney Eli Zohar, and his spokesman from years in the Jerusalem municipality, Haggai Elias, were also employed by the project entrepreneurs.

The museum’s site, at the corner of Independence Park in downtown Jerusalem, was chosen after a number of other locations were rejected − among them plots near the museums on Givat Ram, the old nature museum in the German Colony and even property in East Jerusalem. The site chosen was familiar to everyone as a parking lot, which had been serving those who visit the city center since the 1960s. Apparently nobody remembered that people were buried there.

“Am Yisrael chai (the people of Israel live),” declared California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in his American-Austrian accent at the museum’s groundbreaking ceremony, in May 2004. It was Schwarzenegger’s first visit outside the U.S. as governor. Next to him on the dais was Moshe Katsav, then the Israeli president. During his meeting with then-foreign minister Silvan Shalom, Schwarzenegger said that building museums of tolerance would promote tolerance just as building fitness clubs promoted health. It was a meeting of two worlds: Hollywood and the subterranean.

Museum of Tolerance Special Report / Part II: Secrets from the grave: Haaretz

Round-the-clock work, long shifts and unprecedented security characterized the five-month excavation of the cemetery on the museum site, where sources say more than 1,000 skeletons were unearthed.

By Nir Hasson

The earthworks

The first one to excavate the site and come upon human remains was archaeologist Gideon Sulimani. Sulimani, a senior archaeologist with the Antiquities Authority, would come to play a key role in the affair. In December 2005 he began a “rescue excavation” financed, as mandated by Israeli law, by the Simon Wiesenthal Center, intended to remove antiquities, or in this case, human bones, before the area was cleared for construction.

The act of excavation thrills Sulimani, from a scientific point of view. A serious excavation, says Sulimani, could open a window into the lives of Jerusalem’s Muslim residents over the past millennium. In this case, however, he says that there was pressure on him to hurry up and remove the graves without adhering carefully to professional standards.

“They constantly wanted to lengthen the work days and I was always fighting to shorten them. They told me: Switch teams, work in shifts. But I can’t bring someone into someone else’s excavation. That’s something that is not done,” he says.

The pressures Sulimani faced during the excavation were also typical, apparently, of the next part of the works. After the High Court ultimately rejected the Islamic Movement’s petition, in October 2008, and thus permitted work at the site to continue, the digging was resumed with greater urgency. Testimony obtained by Haaretz indicates that the guiding principle of the work was not a careful and scientific archaeological excavation, one that was respectful of the remains found at the site, but rather an excavation that proceeded as quickly as possible so as to leave the whole skeleton affair behind, so that full attention could be turned to building the Museum of Tolerance.

“We were like a small army, made up of workers, and area managers above them, and the archaeologists above them,” is how one worker summed up what life was like for him and his co-workers at the time. “From 40 to 70 workers per shift. You have to arrive 15 minutes before your shift and wait by the gate. The guy in charge comes with a list of names and lets people in one by one. You have to show ID at the entrance. Then they take your phone and you have to wait at the side until the previous shift collects its things …. The skeletons themselves were disintegrating, whatever comes out comes out, if you can put it in a box you do, and if it’s crumbling you leave it.”

Unlike the vast majority of archaeological excavations in Israel, in this excavation the work was carried out around the clock, in three eight-hour shifts. The workers were recruited by word of mouth, and the attractive wages that were being offered drew in numerous willing laborers. Pay ranged from NIS 35 to 40 per hour, and was even higher during the night shift. The standard wage in archaeological excavations is about NIS 25 per hour. The cost of the excavations is not known, but figures provided by the Moriah company and published on the company’s Web site indicate that Sulimani’s initial excavation, which was of shorter duration and less intensive, cost NIS 3.5 million. The excavation last year presumably cost more than that.

Also present at the site were supervising archaeologists from the Antiquities Authority, contractors, and the senior archaeologist in the field, Dr. Alon Shavit, who was also the owner of a private company that employed the laborers on the site.

According to testimony obtained by Haaretz, Shavit and those in charge at the work site urged the excavators to speed up the work as much as possible.

In the first weeks, the work was done with great meticulousness: Each skeleton that was unearthed was carefully cleaned, documented with photographs and a sketch, and then excavated as gingerly as possible and transferred to cardboard boxes for eventual reburial elsewhere on the site. But the workers attest that as time went on, and more and more graves and bones were uncovered, the pressure from management increased and the work became steadily sloppier. “After a month and a half to two months, the priority was speed,” said A., one of the workers. “Moving the skeletons as fast as possible in order to reach the bedrock − the rock beneath which there are no more graves − they were always telling us to ‘move it, move it.’ So we didn’t have time to do a sketch − that’s okay; soon it’s going to rain, soon the tractors will be coming, we have to hurry.”

N., another worker, said: “[We were expected to] work quickly, those were the managers’ orders. Twenty-four hours. Three shifts of eight hours. From 7 A.M. to 3 P.M., 3 P.M. to 11 P.M., and 11 P.M. to 7 A.M. It wasn’t archaeology, it was contract work. At first they would draw and photograph everything, but by the end it was just, quickly take out the skeletons and put them in boxes. The poles of the tent where we doing the excavating fell down, it was full of mud. They would pressure us: ‘You have 15 minutes to take the skeleton out,’ they wanted us to work as fast as possible.”

The workers say that some of the skeletons were damaged as a result of the work. The new breaks are identifiable by a light-colored fracture line, as opposed to the old breaks, which are darker. In pictures obtained by Haaretz, it is possible to see skulls and bones that have new fractures in them. It should be noted that the workers themselves say that sometimes the skeletons were in terrible condition and crumbled upon being touched, but frequently the skeletons were damaged as a result of work with unsuitable tools.

A. added that according to the procedure the skeletons were put in cardboard boxes, and “sometimes, several skeletons were removed at once, and if they couldn’t take each one out separately, they were put into the same box all together.” Bones that fell were put into “scattered” boxes. The boxes full of bones were then transferred to a container situated at the edge of the field.

Added N.: “People walked on them [the skeletons]. I talked about it with the workers, but they said to me, ‘Did they already pay you?’ I didn’t feel good about it, but I told myself better it was me and not someone else.”

It must be remembered that some of the skeletons at the site were hundreds of years old, and most were in a process of decay before the excavation workers ever got to them. The workers say the trickiest part was removal of the skulls, which, said one, “would disintegrate at the slightest touch.”

On the other hand, it seems, no special efforts were made to minimize the damage to the graves, as the project’s heads had proposed doing in response to the High Court ruling. In two out of the three methods the developers had suggested, the skeletons were to be moved to an alternative burial site while still encased in the the earth surrounding them.

Most of the work was done in the winter months under difficult weather conditions. Despite the use of “hothouses” − large tent-like structures under whose cover the excavation work was carried out, the workers describe difficult conditions: “It was freezing cold, there was rain, tons of hail. Every once in a while they stopped the work to bring in water pumps,” says A. Overseeing the workers doing the excavating there were shift managers, or area managers, on site. These were mostly bachelor’s or master’s degree students in history or similar departments, and “it wasn’t what they thought they were going to be doing. They expressed a lot of resentment, but not to the people in charge. There were people who left. Those who stayed did it for the money,” said A. The fact that, unlike most archaeological excavations in Israel, no Palestinian workers took part in this excavation, can be seen as an indication of the sensitivity of the project.

At the time of Sulimani’s first excavation season, in 2005, Haaretz published workers’ accounts of the nature of the work. This time, the developers had clearly decided that this wouldn’t happen again: Security procedures at the site were unprecedented for either an archaeological excavation or civilian construction site.

According to testimony obtained by Haaretz, two or three guards were always posted at the entrance to the site. “It was like a checkpoint, not just a doorway,” said N. On arrival, workers had to hand over their cell phones to the security personnel. They were also searched, upon both entering and departing.

“They would take anything that looked like an electronic device, even a music player,” added A. During the shift, the excavation workers were not allowed to leave the site, not even to buy food. “The archaeologists were permitted to leave and they would buy for us.” The security cameras at the site pointed not only outward, but also inward, in order to keep an eye on the workers. In one corner of the site was a security trailer where an “operations sergeant” watched the camera images on screen.

The message to the workers was clear: “It was like being in the army. You need to keep quiet,” said N. To drive home this message, the workers were also asked to sign a confidentiality agreement prohibiting them from talking to anyone about what they saw on the job.

The Simon Wiesenthal Center supplied the explanation for the security measures, by citing the threats that had been made to cause harm to the site and the workers. In tandem with the security measures, the workers say there was an effort to boost morale. “They were always telling us that we were doing important work,” says A.

Sulimani and other archaeologists are highly critical of the work methods at the Museum of Tolerance site. One thing that seriously disturbs them is the fact that work was carried out in shifts, and continued through the night. “Shift work does not allow for a processing of the material. You can’t bring someone else into an excavation. It’s something that’s not done. They call this an archaeological excavation but it’s really a clearing-out, an erasure of the Muslim past. It is actually Jews against Arabs,” says Sulimani, who himself is Jewish.

“This method of working in shifts is something that came from the world of industry, and is not suitable for an archaeological excavation,” adds Rafi Greenberg, an archaeology lecturer from Tel Aviv University, who submitted an expert opinion to the High Court critical of the Antiquities Authority’s conduct in the affair. “Basically, in Israel today, because bones are not defined as antiquities, there is no way of ordering the excavation of a cemetery in a thoroughly scientific fashion. In another country, they would devote years to such an excavation, and also build a special lab to analyze the results. There’s a circle here that can’t be squared. It’s impossible to scientifically excavate a cemetery that holds thousands of skeletons. You have to make compromises. If you give up on preserving the bones, then what you get are dust and skeleton fragments.”

A senior archaeologist who also visited the excavation had the following to say about the way it was being run: “It’s very unusual. They wanted to finish the whole story as fast as possible. It’s a known method. They wanted to create a done deed, after which people could yell all they wanted to, but there wouldn’t be any graves left anymore.”

The rain and mud, say the archaeologists, also did not make for a serious scientific excavation that would lead to the skeletons being removed delicately and intact. Nor did the secrecy surrounding the excavation add to its professionalism, they say.

“Archaeology that is done behind walls cannot be scientific,” asserts Sulimani, adding: “You have to forget about the romance of the profession. Archaeology is land and land is real estate and real estate is worth a lot of money.”

The Israel Antiquities Authority would not say how many skeletons have been removed from the Museum of Tolerance site, and passed the query to Alon Shavit, who did not respond to the question. The Wiesenthal Center responded to questions from Haaretz on that issue by saying that “the developers did not and could not interfere with the excavation rescue works, and that the archaeological project was licensed to Tel Aviv University, and the work on the site was conducted by Dr. Alon Shavit.”

Among the workers and the archaeologists, the numbers vary. But all those interviewed by Haaretz agree that no fewer than 1,000 skeletons were excavated at the site. One worker, who was familiar with the numbers as part of his job, puts the figure at more than 1,500. The only serious scientific examination done at the site, by Sulimani, indicated there were 1,000 skeletons, a number that concurs with the workers’ accounts.

The skeletons that were removed were transferred for reburial in a common grave inside the fence of the work site, in a long and narrow strip along the site’s eastern boundary, which falls in the area of of the Muslim cemetery. Therefore, the museum will not be built on the reburial site of the skeletons.

The toughest questions have to do with the propriety of the excavation management. Essentially, on the basis of the affidavit of the Antiquities Authority and the High Court ruling, in most of the museum area the developers were permitted to go ahead with the work even without a need for archaeologists.

“They could have come with bulldozers and cleared the area,” says Sulimani. The ruling required archaeological supervision only in one part of the site, the so-called “purple area.” In this area the developers were also obliged to exercise utmost caution in regard to the skeletons. In actual fact, say the workers, there was no difference between the purple area and the other areas of the site. Despite the declarations to the High Court, skeletons were excavated from different areas with a level of care that was dependent on time pressure and the excavators’ level of professionalism.

Shavit served in a dual capacity. He carried out actual archaeological work as director-general of the Israel Institute of Archaeology, an organization affiliated with Tel Aviv University that received the excavation license from the Antiquities Authority. On the part of the site where an excavation license was not needed, he was a private contractor who was hired by the Wiesenthal Center to remove the skeletons. He was also the expert who recommended to the High Court that the skeletons be excavated by hand.

The third part of this report is available here, and cannot be placed on this page due to space limitations.