EDITOR: After the most anodyne and hapless election, what now?

Israelis have spent the last few months avoiding reality in the most unreal election campaign, avoiding the issues and avoiding the future. Now it seems, that the winner of the day is the greatest avoider of all, Yair Lapid, leader of Yesh Atid, which in Hebrew means “There is a Future”…. indeed. He, who spoke about a future ona different planet, may hold the keys for the next government. As he has no politics, he could sit with Netanyahu and Bennett as easily as he could with Yachimovich and Livni. On paper, the ‘left’ and ‘right’ are equal, but this is only true in cloudcukooland. In Israel reality, no government is ever built with the Arab parties, of course. So there is hardly a way for the ‘centre left’ to build a government, while it is also difficult, but not impossible, for Netanyahu to build a wide government. Israel being what it is, that is what is likely to take place, with Lapid to give it a shade of mock respectability. Woe to us all.

When an apolitical candidate is the big winner of an apolitical election: Haaretz

Israel made a decisive statement regarding what it wants: it wants only to be left alone, a quiet, good life, peaceful and bourgeois, and to hell with all those pesky nagging issues; Lapid epitomizes this attitude.

A patently apolitical candidate has become the big winner of the most patently apolitical elections ever held in Israel. A former columnist and TV presenter, who rarely wrote or spoke of political issues, not in his political columns nor in his TV weekly magazine, made an instant switch to politics, even then not uttering much in the way of political statements. On Tuesday, Israel gave him a resounding “yes!” Yes to the young, yes to the new, yes to the apolitical. He was anointed as crown prince, second in importance only to King Bibi, who turned out to be almost naked. Had it not been for the union with Yisrael Beiteinu, it is doubtful if Likud would have been the largest party in the coming Knesset. A hollow election campaign has resulted in an equally empty result – a bit of everything and a lot of nothing.

Israeli elections yet again ended in a draw – a tie between left and right, if those are the correct terms in Israel. The elections deflated the Bennett legend, with Habayit Hayehudi turning out to be another Shas in the number of seats it won, no less and no more. Not what we thought and not what we feared. Israel on Tuesay voiced a very hesitant “yes”, which was almost a “no”, to the aspirations of Shelly Yacimovich to become a real alternative to Netanyahu. The party she heads will not even be the second largest in the Knesset, to its shame. This signals the end to her pretensions to reconstruct the Labor party, counting on drawing strength from the social protests two summers ago and from masses of young-old voters, obedient and conformist, who ended up not delivering the goods. Her dreadful sleight of hand, attempting to hide the occupation under the carpet, did not help her much.

In contrast, Israel said “yes” to a straight shooting party such as Meretz, which doubled its strength in a dignified showing. Israel also said “no” to the fragments of tiny parties that did not pass the electoral threshold. The good news: the racist Otzma Leyisrael as of this writing is out. The bad news: as of this writing, the subversive “Eretz Hadasha” (new country) didn’t make it either.

Above all, Israel made a decisive statement regarding what it wants: it wants nothing, only to be left alone. Voters want a quiet, good life, peaceful and bourgeois, and to hell with all those pesky nagging issues. Lapid epitomizes this attitude, being the role model for the all-Israeli dream. He looks good and dresses well, he’s well-spoken and well-married, lives in the right neighborhood and drives the right kind of Jeep.

With that, he doesn’t say much. He’s not extreme, heaven forbid, that’s not who we are, nor does he stick his hand in the fire, that’s not us either. He stays away from any divisive issues, just as Israelis prefer. Even when they took to the streets in that magical summer of 2011, remnants of which event were still evident yesterday, their protests turned out in retrospect to be encapsulated only in songs by popular singers Shlomo Artzi and Eyal Golan, without real substance. Lapid fits this mold perfectly, as characterized by protest singing in the city square, with no clear agenda and angry protest. “Let us Live in Peace” was the slogan of the General Zionist party in the 1951 elections. Let us live in this land was the slogan of many Israelis yesterday. Let us live without Arabs and Haredi Jews, without wars and terror attacks, without the world and its preaching. Now, as it was then, this represents pure escapism. Yesterday, Israel affirmed escapism.

On Tuesday, Lapid acquired power that he most likely did not anticipate, and that he may not know what to do with. It is difficult to know if he can put some content behind the power given to him, but perhaps there is room for hope. For someone who managed to change his conduct and mannerisms in the course of the preceding campaign, shedding some of those that characterized his columns and TV appearances, growing and maturing in the process, it is possible that he will grow into the role thrust upon him yesterday. Perhaps with the power will also come some meaningful utterances and a willingness to fight.

A new day is dawning upon us, a dawn of a day in which Israel only wants to be left alone with all its comforts. Only grant it Lapid and quiet, the terrible quiet at the brink of the abyss.

EDITOR: And while the pundits are punditting, apartheid strikes in total immunity!

PHOTOS: Jordan Valley demolitions leave Palestinian families homeless in winter: 972mag

On January 17, the Israeli army destroyed 55 homes and animal shelters in the Al Maleh area. This large scale military operation happened simultaneously in two separate locations: Hamamat al-Maleh, and further up the valley in Al-Mayta. Al-Maleh and Al-Mayta are two marginalized villages located in the north of the Jordan Valley, near the Tayasir checkpoint.

Of the 55 buildings demolished, 23 were family homes: five in Hamamat Al-Maleh (leaving 37 people homeless) and 18 in Al-Mayta (leaving 150 people homeless). In addition, 33 other buildings used to shelter the communities’ animals were destroyed, as well as some water tanks. Two days later, on January 19, the entire village had been declared a Closed Military Zone and the Israeli army confiscated the community’s possessions, including food, bedding and tents that had been provided to the families by the Red Cross after the demolitions. However, the residents stayed and slept out in the fields with no shelter.

Both Al-Maleh and Al-Mayta, like many villages in Area C, have suffered a continuous pattern of harassment by the Israeli army. They have been subject to repeated demolition orders and only two weeks ago were forced to leave their homes for one night, purportedly due to Israeli military training.

To see the rest of the photos, use the link above

Yair Lapid: The rise of the tofu man: 972mag

Despite an astonishing surge to second place in the polls, chances of Yair Lapid making an actual premiership bid are slim. He is risk-averse, lacks a political program, and his projected coalition is too fanciful to work. Lapid is much likelier to join Netanyahu’s next government, and the only question is: Will Lapid be Bibi’s pretty face in Washington as Foreign Minister, or will he be the Finance Minister, and therefore fall guy, for Israel’s upcoming austerity drive?

LIKUD VICTORY RALLY, TEL AVIV – After months of predictions for a comfortable right-wing win, Israel reeled tonight at a surprising near-gridlock between the “Right” and “Left” parliamentary blocs, with the Netanyahu-Liberman union barely scrambling past 30 seats, instead of the 45 42 they held between them in the departing parliament. But Netanyahu’s ratings were in steady decline ever since the union pact in late November and not least thanks his petty and paranoid attacks on settler leader Naftali Bennett. The true surprise of the landslide vote was ultra-centrist candidate Yair Lapid. Lapid, a TV personality who avoided taking any remotely controversial stand on almost any issue, careened past rivals right and left to end up with 17 to 19 seats, rendering him the kingmaker of these elections. Bennett himself, the other golden boy of the 2013 elections, is currently forecasted to win 12 seats, a solid achievement but a far cry from the utopian poll projections of 15-19. Kadima, the centrist party that led Israel to wars in Lebanon and Gaza during its first term in the Knesset, and imploded in a series of ill-judged political manoeuvres at the end of its second term, has not made it to a third term at all, evaporating from Israeli politics with zero seats in the exit polls.

On the Left, Shelly Yacimovich doubled Labor’s seats but fell far, far behind her promise to oust Netanyahu or even to restore Labor as a significant force in Israeli politics. To add insult to injury, after making every possible effort to depoliticise and centralise Labor’s toxic brand, she was overtaken by an ad-hoc party led by a man who lacks any of the political structures, networks and traditional strongholds of Labor, but whose neutral and consensual public image made him more apolitical than she could ever hope to be. The great winner on the left side of the map is Meretz, raised from the dead by new leader Zehava Galon to go from three to seven seats; unlike Labor, Meretz never harboured illusions about premiership, so it can be content with its significant victory. Hadash, the only Jewish-Arab party running, is left with four seats, having failed to rejuvenate its front ranks and thus also failed to capitalise on the social justice movement in which its activists played a significant part (stay tuned for separate stories on social justice and Hadash tomorrow).

Theoretically (or rather, purely arithmetically), Lapid is now in a position to make a bold bid for premiership. Although earlier attempts to herd the centre-leftist cats into a unified bloc ahead of the elections failed miserably, the tantalisingly small gap between the Left and Right in the exit polls could give Lapid enough of a momentum – to hammer together a centre-left government of small parties, to persuade Shas to switch sides (by reminding them they’d hold much more sway in such a fractured coalition than in a strong right-wing one), and to solicit the external support of Arab parties (among which Hadash is usually lumped), eventually creating something akin to Rabin’s government in 1992. But, to the tune of “you are no Jack Kennedy,” Lapid is no Rabin, and 2013 is not 1993. Lapid is risk-averse and lacks a political program or vision; while the negotiated two-state process, a novel idea in Rabin’s time, has been tested and failed in the 21 years since. What’s more, hostility towards the Arab parties is immeasurably greater than it was in the 1990s. Any party overpowering the Right with these parties’ support will be seen as an usurper. Lapid may well launch a bid for premiership – but this is likely to be a negotiation ploy designed to mark him as not just a coalition member, but a partner in a “national unity” government, a title with considerably more clout and gravitas.

Poison, sir?

The more likely outcome, then, is a strong right-wing government with Lapid’s party as its safety belt and fig leaf. In such a scenario, Lapid can look forward to appointment as foreign minister, which would reward him with prestige and the limelight he is long accustomed to, and would reward Netanyahu with a telegenic, charismatic and unoriginal moderate face in the world arena. If Netanyahu sees Lapid more as a rival than a partner, however, he might offer him the Finance Ministry instead – a poisoned chalice if there ever was one. While a highly prestigious position and well in tune with (upper class) Lapid’s self-appointed role as emissary of the middle class, the Treasury is the least enviable fiefdom Netanyahu can offer anyone. Israel is facing an NIS 40 billion deficit and is poised on the brink of an austerity drive set to affect primarily Lapid’s own electorate; getting him to deliver the blow to his own crowd will neutralise him even more effectively than leaving him out of government. The same, with slight amendments, applies to Naftali Bennett and several other candidates; the Finance Minister appointment will tell us where Netanyahu sees the greater threat – from the Centre or from within the Right – and who he considers his most dangerous rival.

If she holds by her vow never to enter Netanyahu’s government (even if he offers her, say, the Finance Ministry), Yacimovich now has the opportunity to forge a combative and determined opposition. Such a move, if played patiently and committedly, will pay off with interest over the long term, especially in the wake of the anticipated austerity drive. This move can be impeded not only by tempting offers from Netanyahu, but primarily from within Labor – the most patricidal (or matricidal) party in Israeli politics. The knives will be out for the leader whose campaign was characterised by self-promotion and by a neglect, to put it mildly, of some of the strongest potential Labor candidates who came into the party of their own accord (Stav Shaffir and Merav Michaeli being the lead examples,) in favour of loyal but utterly lacklustre apparatchiks.

Tomorrow morning Israel will wake up to the real results fairly similar to the exit polls (despite the latter’s margin of error), and while a complete tie between Right and Left or a slight advantage to the Left can generate a modest momentum for an attempted leftist government, the right-by-centre-right coalition is the likeliest outcome. The only question is how tough a negotiator Lapid will prove to be – he could condition his entry into government on, say, complete exclusion of all ultra-Orthodox parties – and how protracted negotiations will be as a result. This might be more significant than a mere inconvenience: Israel is currently without a budget (Netanyahu threw down the cards on budget negotiations in the spring as pretext for gambling on elections) and is weighed down by a 40-billion-shekel deficit. Delay in putting together the team that will cover up that black hole will make the fabled Israeli stock exchange very antsy and drive a pin into Israel’s financial stability balloon – setting the stage for a much more heated contestation over economy, far from the Right’s familiar playing field.

The success of Israel’s social protest failure: Haaretz

While Tuesday’s election was in many ways about the social protests in Israel in 2011, it did not address the most pressing social ills and only perpetuated the false dichotomy between right and left.

By Lev Grinberg | Jan.23, 2013 | 2:12 AM

Tuesday’s election in Israel revolved around the success of the social protests of the summer of 2011 — and also their failure. If we cannot comprehend this paradox then we cannot easily comprehend the bizarre and surprising campaign we just witnessed — and what it is expected to bring.

There is nothing extraordinary about this paradox. It is the nature of protest movements to succeed only in part because they are not political parties, and the existing parties always try to gain political capital on Election Day from the protests.

The Israeli Black Panther movement, for example, erupted, like all social protests, during a period of military calm (1971-73), and it shook up the political system. The Panthers protested against anti-Mizrahi discrimination and voiced their anger at an establishment that absorbed them as immigrants and then relegated them to the social, economic, geographic and cultural periphery. “The second Israel,” they were called, or edot hamizrah (communities of the east), to underscore their inferiority.

Even though it comprised only a few thousand young and inexperienced demonstrators, the Panthers’ protest made enormous gains in changing the public discourse about Mizrahim. It also succeeded in changing economic policy and in transforming Israel from a hand-out state into a welfare state.

But the Panthers’ success helped Likud to mobilize Mizrahi anger without having to represent Mizrahi interests. The peripheral Mizrahim voted for Likud in order to bring down the Labor Alignment, which had discriminated against them. But they got stuck on the “right” and the Mizrahi voice was suppressed repeatedly, by both the right and the left. The economic situation of some Mizrahim has improved since the 1970s, thanks both to the welfare policies introduced by Labor Party precursor Mapai and Likud’s rise to power. But others remained stuck in the periphery and in difficult economic circumstances. At the same time, the legitimacy for speaking in the name of anti-Mizrahi discrimination was lost: For proof, look at Shas.

The reference to the Black Panthers was not accidental. This election revolved around the discourse that was created in that era, a discourse of left and right and the Ashkenazi hegemony that silences any voice that lays it bare. Hatred of Shas was a common denominator of this election, in parties from Habayit Hayehudi on the right to Meretz on the left — a wall-to-wall coalition.

This points up one of the most glaring failures of the recent social protest movement: its inability to combine the discourse of equality and social justice with the need for affirmative action for groups within society that the regime oppresses: Mizrahim on the periphery, the ultra-Orthodox, Arabs, Ethiopians, some Russian-speakers and above all, Palestinians in the territories.

The reign of the business tycoons would not be possible without dividing and sowing strife among these various groups. A universalist discourse on behalf of justice and equality is insufficient, because justice and equality only for some immediately become injustice and inequality.

To my mind, the most serious failure has been the preservation of the left-right discourse, which silences any substantive debate on all the issues on the agenda, including those relating to the Palestinians. But above all, the “left-right” discourse silences issues of economic and social policy, because the poor can be found on both sides of this divide and they have not succeeded in uniting against the rule of the wealthy. Ever since 1977 Likud and Labor have imposed this left-right dichotomy in order to preserve their power and prevent rivals from entering the arena.

And that is what happened in the recent election season: Even though the socioeconomic agenda was in the background throughout the campaign (from the joint slate formed by Benjamin Netanyahu and Avigdor Lieberman to the resignation from the cabinet of Moshe Kahlon and his appointment to a different post at the last moment), there was no new political language. We went back to talking about left-wing and right-wing blocs even as both are crumbling, divided and strife-ridden, and the public feels that every word uttered by the politicians is empty: symbols that stand for nothing. Peace, security justice, equality — everything is included, and it’s all hollow.

They talk about natural partners, about one’s political home. But politics is the opposite of nature: It’s about changing reality: about interests, positions, disagreements, building coalitions to deal with the state’s major problems, formulating policy and implementing it. All these were absent from this election. And therefore, the day after the election, when the results are already known, all the questions will still be before us, but the public won’t be involved in how they are decided. It’s a facade of democracy.

This, too, is an expression of the social protest’s failure: its inability to create a new political language that links the question of social justice to the regime that discriminates against various groups because of their identity, its inability to overcome the regime of division, of intimidate and conquer. This is the regime that Mapai built and Likud perfected, while in the process building the reign of capital and the tycoons.

The language of the left-right cartel is still with us. The Ashkenazi elites have many parties — all except those of the very poorest, who are set apart out and marked as inferior, the lazy and the exploiters who don’t fulfill their obligations: “the ultra-Orthodox and the Arabs.”

When Shas co-leader Aryeh Deri pointed out the whiteness of the right he was attacked from all sides, and he retreated. But this election revolved around whiteness.

That was precisely the criticism leveled at the leadership of the Rothschild Boulevard protesters in the summer of 2011: its whiteness, its dominance, its failure to represent the periphery and its desire to preserve the power of the middle class — that is, the secular Ashkenazim.

Their supporters will indeed enter the Knesset. But all the others won’t. And I don’t believe they’ll quietly go home. My prediction is that they will yet return to the streets, and someday they will succeed in translating the protest into a political language. There will be other elections.

Israel election setback for Binyamin Netanyahu as centrists gain ground: Guardian

Results give narrowest of victories to the prime minister’s rightwing-religious block

Link to video: Israel takes to the polling booths as Palestinians look onBinyamin Netanyahu suffered a major setback in Israel‘s general election as results gave the narrowest of victories for the rightwing-religious block and a surprisingly strong showing for a new centrist party formed last year, forcing the prime minister to say he will seek a broad coalition to govern Israel.Right wing and allied Orthodox religious parties won half the seats in the Israeli parliament, presenting Netanyahu with a tough political challenge to put together a stable coalition.Netanyahu remains on course to continue as prime minister, as his rightwing electoral alliance, Likud-Beiteinu, is the biggest party after winning 31 of 120 seats in the next parliament. But it was a sharp drop from the present combined total of 42 for the two parties.Yesh Atid, a new centrist party led by the former television personality Yair Lapid, won 19 seats. It concentrated its election campaign on socio-economic issues and removing the exemption for military service for ultra-orthodox Jews.

Netanyahu called Lapid, whose unexpected success hands him a pivotal role in coalition negotiations, as the final results came in to discuss a potential government.

Likud officials quoted the Israeli prime minister as telling Lapid: “We have the opportunity to do great things together”.

But Netanyahu was also putting out feelers to ultra-Orthodox parties which could prove vital in putting together a government, saying he would open coalition talks with them on Thursday.

Final results could shift, although not dramatically, later in the week after votes from serving members of the military are counted.

Two out of three Israelis voted in Tuesday’s election, a slightly higher proportion than in the previous two elections, surprising observers who had predicted a fall in turnout.

In a speech at his election headquarters in Tel Aviv, Netanyahu said: “I believe the election results are an opportunity to make changes that the citizens of Israel are hoping for and that will serve all of Israel’s citizens. I intend on leading these changes, and to this end we must form as wide a coalition as possible, and I have already begun talks to that end this evening.”

Lapid told campaign workers in Tel Aviv: “We must now … find the way to work together to find real solutions for real people. I call on the leaders of the political establishment to work with me together, to the best they can, to form as broad a government as possible that will contain in it the moderate forces from the left and right, the right and left, so that we will truly be able to bring about real change.”

Dov Lipman, who won a seat for Yesh Atid, said: “This is a very clear statement that the people of Israel want to see a different direction. We will get the country back on track.”

Labour was the third largest party, with 15 seats. Party leader Shelly Yachimovich said in a statement: “There is no doubt we are watching a political drama unfold before our eyes … There is a high chance of a dramatic change, and of the end of the Netanyahu coalition.” She said she intended to attempt to “form a coalition on an economic-social basis that will also push the peace process forward.” It seems unlikely Yachimovich could present a credible alternative to Netanyahu’s claim to the premiership.

Erel Margalit of Labour said the results indicated “a protest vote against Netanyahu” and that the huge social justice protests that swept Israel 18 months ago “were not a fringe phenomena. Perhaps some of it is moving from the streets into the political arena”.

The ultra-nationalist Jewish Home, which showed strongly in opinion polls during the campaign, was at 11 seats, the same as the ultra-orthodox party Shas. The leftist party Meretz made an unexpectedly strong showing, with six seats, more than doubling its current presence.

Speculation about the composition of the next coalition government intensified as the results came in. Israel’s electoral system of proportional representation has ensured no single party has gained an absolute majority since the creation of the state almost 65 years ago. Negotiations are expected to last several weeks.

As the leader of the biggest party, Netanyahu will be first in line to assemble a coalition. Although Netanyahu’s natural partners are the smaller rightwing and religious parties, he is likely to be keen to include Yesh Atid and possibly Hatnua, which is led by former foreign minister Tzipi Livni and won seven seats. However, Livni’s insistence on a return to meaningful negotiations with the Palestinians could deter Netanyahu from inviting her join him.

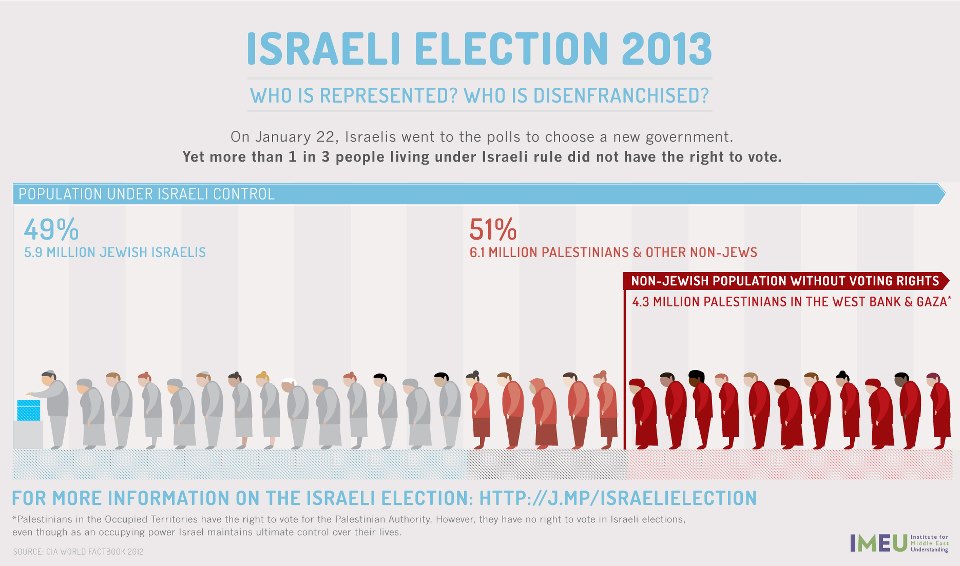

Three parties mostly supported by Israeli Arabs had 12 seats between them. Although they are regarded as part of the left bloc in the Knesset, it is unlikely they would be part of any coalition government.

Yehuda Ben Meir of the Institute of National Security Studies, said: “The story of this election is a slight move to the centre, and above all the possibility of Netanyahu forming a coalition only with his ‘natural partners’ does not exist. He is definitely going to work for a wider coalition.”

According to Ari Shavit of the liberal newspaper Haaretz, Netanyahu had failed to consolidate or advance his party’s position. “While in the past he was given poor cards and played them well, this time he had the best cards and played them badly. This was a lesson in how not to run a campaign.”

Kadima, which was the biggest party in the last parliament with 28 seats, saw its support plummet and only just crossed the threshold of votes needed to win two seats, according to the partial results.

In Washington, the Obama administration said it is waiting to see the make up of the new government and its policies on peace with the Palestinians. But the White House spokesman, Jay Carney, said there would be no change in US policy.

“The United States remains committed, as it has been for a long time, to working with the parties to press for the goal of a two-state solution. That has not changed and it will not change,” he said.