EDITOR: The Arab Revolt has turned viral!

For those who told us that there is nothing to worry about the Gulf joining in the wave of protest, Bahrain has today proven them very wrong! From Algeria in the west, to Iraq in the East, the revolt is spreading like wildfire. Those who have written off the Arabs as undemocratic, are the same people who have financed and supported the dictators across the Arab world.

Even in those countries where, for reasons of deep fear the population has not yet risen, such as in Syria, Libya, or Saudi Arabia, this is a matter of time. As the regional tyrants fall like domino pieces, each one has less power to support him in position. The question is, will the US and its western poodles learn to live and understand, not to mention value, these amazing developments?

Deaths heighten Bahrain tension: Al Jazeera online

Offering apology, King Hamad vows to investigate incidents but opposition group suspends parliamentary participation.

15 Feb 2011

Al Jazeera’s correspondent in Manama reports on the ongoing unrest in the Bahraini capital

At least one person has been killed and several others injured after riot police in Bahrain opened fire at protesters holding a funeral service for a man killed during protests in the kingdom a day earlier.

The victim, Fadhel Ali Almatrook, was hit with bird-shotgun in the capital, Manama, on Tuesday morning, Maryam Alkhawaja, head of foreign relations at the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, told Al Jazeera.

“This morning the protesters were walking from the hospital to the cemetery and they got attacked by the riot police,” Alkhawaja said.

“Thousands of people are marching in the streets, demanding the removal of the regime – police fired tear gas and bird shot, using excessive force – that is why people got hurt.”

At least 25 people were reported to have been treated for injuries in hospital.

An Al Jazeera correspondent in Bahrain, who cannot be named for his own safety, said that police were taking a very heavy-handed approach towards the protesters.

“Police fired on the protesters this morning, but they showed very strong resistance,” our correspondent said.

“It seems like the funeral procession was allowed to continue, but police are playing a cat-and-mouse game with the protesters.”

The developments came as the king of Bahrain, Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa, made a rare television appearance in which he offered condolences on the protesters’ deaths.

The process of change in the kingdom “will not stop”, the official Bahrain News Agency quoted Sheikh Hamad as saying on Tuesday.

Opposition’s move

Angered by the deaths, a Shia Muslim opposition group has announced it was suspending its participation in the parliament.

“This is the first step. We want to see dialogue,” Ibrahim Mattar, a parliamentarian belonging to the al-Wefaq group, said. “In the coming days, we are either going to resign from the council or continue.”

Al-Wefaq has a strong presence inside the parliament and within the country’s Shia community.

Video from YouTube showing riot police firing on largely peaceful protesters during Monday’s demonstration

Tuesday’s violence came a day after demonstrators observed a Day of Rage, apparently inspired by the recent uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia.

Shias, who are thought to be in the majority, have often alleged discrimination at the hands of the kingdom’s Sunni rulers.

Thousands came out on the streets on Monday to protest, sparking clashes with riot police.

Khalid Al-Marzook, a Bahraini member of parliament, told Al Jazeera that one person had been killed and that three others were in critical condition in hospital following Monday’s violence.

Bahrain’s news agency said that the country’s interior minister had ordered an investigation into Monday’s death.

The interior ministry later issued a statement saying that “some of the people participating in the the funeral clashed with forces from a security patrol”, leading to Almatrouk’s death.

“An investigation is under way to determine the circumstances surrounding the case,” it said.

Lieutenant-General Shaikh Rashid bin Abdulla Al Khalifa has also offered his condolences to the dead man’s family.

Online reaction

Amira Al Hussaini, a Bahraini blogger who monitors citizen media for Global Voices Online, told Al Jazeera that there has been a huge outpouring of anger online in Bahrain.

“What we’ve seen yesterday and today, is a break from the normal routine – people like me, that are not necessarily in favour of the protests that are happening in Bahrain at this time, are now speaking out,” she said.

“I am trying to remain objective but I can’t – people are being shot at close range.”

Hussaini said that people in Bahrain were very afraid.

“We are afraid of going out in the streets and demanding our rights. Tunisia and Egypt have given people in Arab countries hope – even if you believe that something is impossible.”

“I personally have no respect for the police – they lie, they manipulate the story,” she said.

“This is being pitted as a sectarian issue – the Shia wanting to overthrow the regime. But it is not a Shia uprising.”

She said that people from all backgrounds and religions are behind the protests.

EDITOR: Israel is getting used to the new realities?

Below is an articles short on analysis but long on deep worries about the future – Israel is coming to realise, gradually, that the world around it is fast changing, and that the old certainties are gone, probably forever. Its crimes might not be defended in the future by all those who have done so in the past.

Israel faces emboldened Palestinian delegation in the UN: Haaretz

Israel’s new UN ambassador, Ron Prosor, will face an atmosphere of support for Palestinian causes in the UN and an uphill battle in generating sympathy for Israeli causes.

Palestinians are vigorously working to get the United Nations Security Council resolution condemning Israeli settlement building passed. They are working quickly to get support from the organization’s general assembly before Israel’s new UN ambassador Ron Prosor, takes up his position.

Israel will appoint their new UN ambassador after half a year spent with a temporary representative. Prosor, who has been serving as the ambassador in London will soon send his credentials to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon. From there, he will receive the formal authority of a permanent UN ambassador, allowing him to fulfill his role in New York in an orderly way.

Prosor, a veteran diplomat valued in Israel for his work in the foreign service, can expect a difficult time at the UN’s New York headquarters. The list of problems and topics that Prosor will be forced to deal with in the next few months is long and troublesome.

What may surprise him is the degree of sophistication and diplomatic expertise that the Palestinians have become emboldened with in recent months during their work to move their interests forward, especially in behind the screen negotiations.

The new ambassador will soon discover that the absence of negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians has created an atmosphere of support for Palestinian issues, an atmosphere in the manner of which has not been felt in the UN for years.

The political stagnation, for which Israel is responsible, produced a wave of initiatives including the draft against Israeli settlements and the Russian initiative to dispatch a Security Council delegation to the Middle East to closely examine the reasons for the ongoing crisis between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

In addition, ambassadors of central nations in the UN are well aware of the cold relations between the White House administration and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, an awareness which has allowed the atmosphere of criticism towards Israel in the UN continue, even among nations thought to be friendly with Israel.

Israel’s chance to prevent the Palestinians from gaining a majority at the UN on their proposal for an independent Palestinian state is slim. In addition, the new ambassador’s ability to generate sympathy and attentiveness for Israeli claims on topics related to the Middle East in the UN arena is very limited.

High up on Prosor’s list of priorities will be alerting the UN about the strengthening of Hezbollah in Lebanon as well as the ramification of UN resolution 1701, which calls on the Lebanese Army to deploy throughout the country, including in the Hezbollah stronghold of southern Lebanon, and prevent Hezbollah from acquiring more weapons. Another priority will of course be strengthening opposition to Iran’s nuclear program.

Prosor is well known for his work in London against schemes to delegitimize Israel. In the center of the United Nations in New York, he will need all the experience that he acquired in this field.

Egyptian army hijacking revolution, activists fear: The Guardian

Military ruling council begins to roll out reform plans while civilian groups struggle to form united front

Jack Shenker in Cairo

A man takes a picture of his daughter on an Egyptian army tank in Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photograph: Hussein Malla/AP

Egypt’s revolution is in danger of being hijacked by the army, key political activists have warned, as concrete details of the country’s democratic transition period were revealed for the first time.

Judge Tarek al-Beshry, a moderate Islamic thinker, announced that he had been selected by the military to head a constitutional reform panel. Its proposals will be put to a national referendum in two months’ time. The formation of the panel comes after high-ranking army officers met with selected youth activists on Sunday and promised them that the process of transferring power to a civilian government is now under way.

But the Guardian has learned that despite public pronouncements of faith in the military’s intentions, elements of Egypt’s fractured political opposition are deeply concerned about the army’s unilateral declarations of reform and the apparent unwillingness of senior officers to open up sustained and transparent negotiations with those who helped organise the revolution.

“We need the army to recognise that this is a revolution, and they can’t implement all these changes on their own,” said Alaa Abd El Fattah, a prominent youth activist. “The military are the custodians of this particular stage in the process, and we’re fine with that, but it has to be temporary.

“To work out what comes next there has to be a real civilian cabinet, of our own choosing, one that has some sort of public consensus behind it – not just unilateral communiques from army officers.”

There is consternation that the army is taking such a hard line on the country’s burgeoning wave of strikes, which has seen workers seeking not just to improve their economic conditions, but also to purge institutions of bosses they accuse of being corrupt and closely aligned to the old regime.

“These protests aren’t just wage-specific,” said Abd El Fattah. “They’re also about people at ground level wanting to continue the work of the revolution, pushing out regime cronies and reclaiming institutions like the professional syndicates and university departments that have long been commandeered by the state.”

The ruling military council has called on “noble Egyptians” to end all strikes immediately.

Egypt’s post-Mubarak political landscape has grown increasingly confused in the past few days, as the largely discredited formal opposition parties of the old era seek to reposition themselves as populist movements. Meanwhile younger, online-based groups are trying to capitalise on their momentum by forming their own political vehicles, and the previously outlawed Muslim Brotherhood has announced that it will form a legal political party.

After decades of stagnation, the country’s political spectrum is desperately trying to catch up with the largely leaderless events of the past few weeks and accommodate the millions of Egyptians politicised by Mubarak’s fall. “The current ‘opposition’ does not represent a fraction of those who participated in this revolution and engaged with Tahrir and other protest sites,” said Abd El Fattah. But with a myriad of short-lived alliances and counter-alliances developing among opposition forces in recent days, uncertainty about the country’s political future still prevails.

“Despite various attempts to form a united front, there’s nothing of the kind at this point – just a lot of division,” said Shadi Hamid, an Egypt expert at the Brookings Doha Centre. “You’ve got numerous groups, numerous coalitions, and everyone is meeting with everyone else. There’s a sense of organisational chaos. Everyone wants a piece of the revolution.”

This week a number of formal opposition parties, including the liberal Wafd party and the leftist Tagammu party, came together with members of the Muslim Brotherhood and a wide range of youth movements to try and elect a steering committee that could speak with a unified voice to the army commanders and negotiate the formation of a transitional government and presidential council.

Yet those plans have been overtaken by the speed of the military’s own independent proclamations on reform, raising fears that civilian voices are being shut out of the transitional process.

Some senior figures inside the coalition believe the army is deliberately holding high-profile meetings with individuals such as Google executive Wael Ghonim and the 6 April youth movement founder Ahmed Maher in an effort to appear receptive to alternative views, but without developing any sustainable mechanism through which non-military forces can play a genuine role in political reform.

“The military are talking to one or two ‘faces of the revolution’ that have no actual negotiating experience and have not been mandated by anyone to speak on the people’s behalf,” claimed one person involved with the new coalition. “It’s all very well for them to be apparently implementing our demands, but why are we being given no say in the process?

“They are talking about constitutional amendments, but most people here want a completely new constitution that limits the power of the presidency. They are talking about elections in a few months, and yet our political culture is still full of division and corruption.

“Many of us are now realising that a very well thought-out plan is unfolding step by step from the military, who of course have done very well out of the political and economic status quo. These guys are expert strategic planners after all, and with the help of some elements of the old regime and some small elements of the co-opted opposition, they’re trying to develop a system that looks vaguely democratic but in reality just entrenches their own privileges.”

Mubarak’s wealth finally in the spotlight: Ahram online

While granting himself the authority to rule on all corruption cases in Egypt, Mubarak is said to have overseen a regime as well as a ruling family with rampant appetites for ill-gotten wealth

Marwa Hussein, Tuesday 15 Feb 2011

During his 30 years of mandate, the ousted president Hosni Mubarak manipulated the country’s regulations in a way that makes it hard to pursue the president of the republic or to confiscate his wealth. A group called “rekabiyoun” (regulators against corruption) formed by civil servants at the Central Auditing Organization (CAO) denounced the law governing its work as controllers of public money.

“The last amendment made to the law of the CAO in 1998 put the organization under the control of the president while the president is one of the actors that are supposed to be under the control of the CAO”, said Ibrahim Gad, supervisor in the Gharbeya governorate (100 km north Cairo).

This change effectively means that Mubarak would have reviewed and judged any accusations of corruption made against him.

Rekabiyoun has said that they will organize a sit-in in front of the CAO’s headquarter in Cairo tomorrow to denounce corruption and inefficiency in their own organism accusing Gawdat Al-Malt, the head of the CAO, for spreading corruption. They seek the reclamation of the CAO’s complete independence in addition to merging it with the Administrative Control Authority and the Administrative Prosecution Authority, allowing them to punish and not only expose corruption.

According to Gad, before the 1952 coup, the CAO (created in 1942) was independent of the government. He remembers when the head of the CAO resigned in 1950 because the king asked him to omit a contravention concerning LE5000 against his press advisor. “The CAO also unearthed a lot of facts in the case of the fraudulent arms in 1948,” adds Gad.

The situation started to change when an army man was nominated as a head of the organization following the officers’ coup.

“Now the head of CAO has reports of contraventions that reach LE500 billion and he took no serious actions. He said that some issues were politically sensitive; the CAO should not be affected by political sensitivity, he has a role to do.”

George Ishaq, a member of the National Organization for Change, said they were gathering information from friends and connections all over the world about the Mubarak’s family assets and wealth. “To pursue Mubarak and freeze his funds, the actual government should ask the world’s governments to do so, we are trying to make pressures on the government to do so,” says Ishaq.

News and rumors have spread about the Mubarak’s family fortune since the start of the Egyptian revolution. The latest to emerge came yesterday when it was revealed that Gamal Mubarak, the president’s son, has holdings in the investment bank EFG-Hermes through foreign investment funds.

EFG-Hermes, the leading investment bank in Egypt and the Arab world, said on Sunday that Gamal Mubarak’s stake in the bank was limited to an 18 per cent holding in a subsidiary, EFG Private Equity. EFG-Hermes, has listed assets of $8 billion as of 2010.

Many businessmen linked with the Mubarak family have important investments shrouded in suspicion. The biggest land deals in the country were made as direct allocations by the government without competitive tenders and for low prices, including land given to the fathers in law of the fallen president’s two sons.

Questions about the fortune of Mubarak and his family were raised after The Guardian published an article estimating Mubarak’s family fortune could be as much as $70bn according to analysis by Middle East experts. “Much of this wealth is in British and Swiss banks or tied up in real estate in London, New York, Los Angeles and along expensive tracts of the Red Sea coast,” said the article. However there is no proof whether those figures are correct with estimates starting at two billion dollars, as United States officials said a few days after the Guardian published its figures.

On the same night Mubarak stepped down, Swiss authorities announced they were freezing any assets Mubarak and his family may hold in the country’s banks. According to western intelligence sources this may have been too late as Mubarak is alleged to have used his last 18 days in power to secure his fortune by shifting it into untraceable accounts overseas.

“We’re aware of some urgent conversations within the Mubarak family about how to save these assets,” said the source. “And we think their financial advisers have moved some of the money around. If he had real money in Zurich, it may be gone by now.”

In the U.K, a spokesman for Britain’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) said the financial crime agency was looking for assets in Britain linked to Mubarak in case there was any request to seize them. However, Britain has yet to take any measures to freeze the family funds. “Britain has to await a request from Egypt, or from the European Union or the United Nations, before freezing any of Mubarak’s assets,” the SFO spokesman said.

Military worried about Brotherhood, youth want 9 months before elections: Ahram online

Yesterday’s meeting between youth representatives and the armed forces council, the military expressed concern over the Muslim Brotherhood, and the youth said they wanted at least 9 months before elections

Ahmed Eleiba , Tuesday 15 Feb 2011

In the course of the meeting, says Samir, the military expressed their concern over the possibility of the Muslim Brotherhood collecting the lion’s share of seats in forthcoming parliamentary elections.

They went on to explain that in accordance with the timetable now in place, the Constitutional Declaration, which the military council had charged a specially formed committee to formulate, may be finalized within 10 days, put to a referendum within two months, and holding parliamentary elections within four months.

The coalition representatives, who included Google marketing manager, Wael Ghoneim, says Samir, told the military that their coalition, which includes the youth movement of the Muslim Brotherhood, does not want elections before 9 months up to one year, in accordance with a new timetable, which coalition members are currently studying. The coalition representatives agreed that elections should be held in competitive climate that provides an even playing field to all participants.

Egypt faces bumpy ride towards democracy: BBC

By Jeremy Bowen

Protests over pay and jobs have continued despite army calls for them to cease

Just take a drive down some of the main avenues in central Cairo and you can see one of the biggest problems facing Egypt’s new military administration.

The economy is more or less at a standstill, and so is the civil service.

Outside almost every government building at one time or another in the last few days has been a crowd of disgruntled employees.

Grievances that people were forced to swallow during the repressive Mubarak years are pouring out.

Badly paid rank-and-file staff want more money. Often, they are also burning with resentment about bosses they say have enriched themselves.

The armed forces’ fifth communique called for the strikes to stop. If polite requests don’t work, the generals will have to decide what they do next.

If they want to keep people on their side, using force to break strikes will not be a good idea.

The biggest and noisiest demonstrations have been by the police outside the interior ministry.

They pushed forward a uniformed sergeant who was obviously unwell, and raged that they were not given proper medical treatment, while the senior officers had their own hospitals.

Messy inheritance

The Egyptians who were in Tahrir Square saw the police as the old regime’s brutal enforcers. But the striking policemen claimed that in reality they were also victims.

“They made us confront the people than they left us here and ran away,” complained one policeman.

President Hosni Mubarak left behind a big stack of problems. Some Egyptians doubt whether the military, led by 75-year-old Field Marshal Mohammed Tantawi, is up to dealing with its messy inheritance.

How it tackles the job is going to have a big impact on the way that the new Egypt develops.

Mr Mubarak, it is now clear, was ushered out of the door by the army high command.

But he was overthrown by a popular uprising. The people who took part in it expect Field Marshal Tantawi and his men to bring in the changes that they want.

They applauded when the army dissolved parliament, which was elected in a rigged vote, and when it suspended the constitution, which was designed to make sure that Mr Mubarak or his chosen successor stayed in office.

But the army has been at the centre of power in Egypt since a coup in 1952. The system that has developed since then suits the generals very well. Now they are expected to dismantle it. Power and money are hard things to give up.

The military has promised to introduce civilian rule in six months or when elections come. To get to that point some big challenges have to be mastered.

Egypt needs a new constitution, and a renewed political system. If the protesters are to get their wish for democracy, it needs free and fair elections.

Smart move

For the time being the armed forces are getting the benefit of the doubt from most people. But that will change if Egyptians, who now believe that their opinions matter, decide that the generals are taking them in the wrong direction.

One smart move would be to bring new blood into the cabinet, which is still mainly made up of former Mubarak loyalists, and to allow civilians into Field Marshal Tantawi’s top team.

That will stop the idea taking hold that the military wants sole charge of the levers of power. And it could also create a sense that Egyptians are in this together, which might even persuade people to go back to work.

It might also be a useful idea to make moves to seize some of the money that Hosni Mubarak and his family are alleged to have acquired during his 30-year reign.

So far some of his associates have been targeted, but not the family itself. Could an intact fortune have been part of the former president’s severance terms?

That won’t please strikers who think that their time has come.

Israel should see the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions as an opportunity: Haaretz

The Egyptian revolution could usher in an era of freedom in the Middle East. But for it to do so, Arabs and Israelis must break free of the chains of prejudice, history and fear.

By Khaled Diab

Millions of Egyptians have accomplished what many thought was improbable: They defied their dictator and won. After three decades as Egypt’s uncontested leader, Hosni Mubarak’s downfall has understandably been cause for euphoria and celebration in Egypt and across the Arab world.

Egyptians have made history. But now, they need to ensure that this revolution does not become a footnote in their history.

While the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions have inspired ordinary Arabs everywhere, they have been largely met with trepidation and fear in Israel. But as a wave of hope and empowerment begins to ripple through the Arab world, it would be a shame and a grave mistake to continue in “business-as-usual” mode on the Arab-Israeli front.

The changing Middle Eastern landscape is a wake-up call to both sides to transform what were once two competing nationalisms (pan-Arab and Zionist ) into complementary ones. The first step toward achieving this is to acknowledge that not everything is the other side’s fault.

Nevertheless, Israelis worry that rather than heralding the dawn of democracy next door, the unfolding revolution marks the sunset of secularism. The frenzied analogies fixate on Iran and 1979, and assume that the Muslim Brotherhood will spearhead a counterrevolution and orchestrate a theocratic takeover of Egypt.

Though I despise the stifling impact of the Muslim Brotherhood on Egyptian society, I doubt this scenario. While the Iranian and Egyptian revolutions share a common denominator in that both were popular revolts against Western-backed despots that took the world by surprise, there are numerous vital differences between them.

One of the most critical is that Egypt has no “cult” religious revolutionary figure like Ayatollah Khomeini. The nearest to a “face” that the Egyptian revolution has is Mohamed ElBaradei, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, seasoned international diplomat and avowed secularist. The only thing the two men share in common is that they returned home to lead something that they didn’t start.

In addition, the Egyptian Sunni clergy – which has long been subservient to the secular authorities – is generally not involved in politics and is not held in the same kind of awe as its Shi’ite counterpart, which was politicized.

As for the Muslim Brotherhood, it was not only a latecomer to the revolution, but is also largely made up of conservative and rather gray laymen who tend to be drawn from the ranks of professionals, i.e. doctors, lawyers and engineers.

Moreover, Egypt today is not Iran circa 1979. The revolution comes at a time when Egypt, which has long had close contact with the West, has had almost two centuries of modernizing and secularizing experience.

Of course, Israeli fears stem not from whether or not Egypt will become a theocracy – as a friendly theocracy would, I imagine, be all right – but from whether or not the new order will be more hostile to an Israel feeling isolated and insecure.

The Muslim Brotherhood is probably the most hostile party to Israel. However, suspicion, distrust, dislike and fear of Israel cut across party lines, both out of sympathy for the plight of the Palestinians and out of the humiliation Israel has heaped on the wider Arab world. This probably means that the cold Egyptian-Israeli peace will become frostier.

Nevertheless, pragmatism is likely to prevail, and I don’t think any likely Egyptian government would risk reneging on the peace agreement. The army has already demonstrated this with its statement that Egypt will respect all its foreign agreements.

For Israel, the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions should be taken not as a threat but as an opportunity. Israelis need to realize that the road to their security lies not through Cairo, but through Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza.

As the Palestine Papers and before them the Oslo Accords clearly demonstrate, along with Israel’s nonreaction to the Arab Peace Initiative, Israeli intransigence, founded on military might and superpower sponsorship, is no substitute for justice. Authority built on oppression, as Mubarak found out, inevitably crumbles.

Following the revolution, Egyptians would be justified in keeping their economic distance from Israel, but they need to stop cold-shouldering Israelis, because this fuels the popular fear that Arabs are not after peace with Israel, but its defeat and destruction by any means possible. The only way to allay these worries and build the necessary popular groundswell for peace is to engage in a direct, grass-roots conversation and dialogue.

The Egyptian revolution could usher in an era of freedom in the Middle East. But for it to do so, Arabs and Israelis must break free of the chains of prejudice, history and fear.

The author, an Egyptian by birth, is a Brussels-based journalist and writer. He writes a regular column for The Guardian and contributes to other publications in Europe, the Middle East and the United States.

The Arab world is dead, but the Egyptians may revive it: The Guardian CiF

Egypt’s revolution has not just deposed a dictator, it has breathed life into an exhausted idea: Arab self-determination

Hussein Agha and Robert Malley

The protesters on the streets of Cairo who, in just 18 days, ended the three-decade rule of Hosni Mubarak were not merely demanding the end of an unjust, corrupt and oppressive regime. They did not merely decry privation, unemployment or the disdain with which their leaders treated them. They had long suffered such indignities. What they fought for was something more elusive and more visceral.

The Arab world is dead. Egypt’s revolution is trying to revive it.

From the 1950s onwards, Arabs took pride in their anti-colonial struggle, in their leaders’ standing and in the sense that the Arab world stood for something, that it had a mission: to build independent nation-states and resist foreign domination.

In Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser presided over a ruinous economy and endured a humiliating defeat against Israel in 1967. Still, Cairo remained the heart of the larger Arab nation – the Arab public watched as Nasser railed against the west, defied his country’s former masters, nationalised the Suez canal and taunted Israel. Meanwhile, Algeria wrested its independence from France and became the refuge of revolutionaries; Saudi Arabia led an oil embargo that shook the world economy; and Yasser Arafat gave Palestinians a voice and put their cause on the map.

Throughout, the Arab world suffered ignominious military and political setbacks, but it resisted. Some around the world may not have liked the sounds coming from Cairo, Algiers, Baghdad and Tripoli, but they took notice. There were defeats for the Arab world, but no surrender.

But that world passed, and Arab politics fell silent. Other than to wait and see what others might do, Arab regimes have no clear and effective approach towards any of the issues vital to their collective future, and what policies they do have contradict popular feeling. It is that indifference that condemned the leaders of Tunisia and Egypt to irrelevance.

Most governments in the region were resigned to or enabled the invasion of Iraq; since then, the Arab world has had virtually no impact on Iraq’s course. It has done little to achieve Palestinian aspirations besides backing a peace process in which it no longer believes. When Israel went to war with Hezbollah in 2006 and then with Hamas two years later, most Arab leaders privately cheered the Jewish state. And their position on Iran is unintelligible; they have delegated ultimate decision-making to the US, which they encourage to toughen its stance but then warn about the consequences of such action.

Egypt and Saudi Arabia, pillars of the Arab order, are exhausted, bereft of a cause other than preventing their own decline. For Egypt, which stood tallest, the fall has been steepest. But long before Tahrir Square Egypt forfeited any claim to Arab leadership. It has gone missing in Iraq, and its policy towards Iran remains restricted to protestations, accusations and insults. It has not prevailed in its rivalry with Syria and has lost its battle for influence in Lebanon. It has had no genuine impact on the Arab-Israeli peace process, was unable to reunify the Palestinian movement and was widely seen in the region as complicit in Israel’s siege on Hamas-controlled Gaza.

Riyadh has helplessly witnessed the gradual ascendancy of Iranian influence in Iraq and the wider region. It was humiliated in 2009 when it failed to crush rebels in Yemen despite formidable advantages in resources and military hardware. Its mediation attempts among Palestinians in 2007, and more recently in Lebanon, were brushed aside by local parties over which it once held considerable sway.

The Arab leadership has proved passive and, when active, powerless. Where it once championed a string of lost causes – pan-Arab unity, defiance of the west, resistance to Israel – it now fights for nothing. There was more popular pride in yesterday’s setbacks than in today’s stupor.

Arab states suffer from a curse more debilitating than poverty or autocracy. They have become counterfeit, perceived by their own people as alien, pursuing policies hatched from afar. One cannot fully comprehend the actions of Egyptians, Tunisians, Jordanians and others without considering this deep-seated feeling that they have not been allowed to be themselves, that they have been robbed of their identities. Taking to the streets is not a mere act of protest. It is an act of self-determination.

Where the United States and Europe have seen moderation and co-operation, the Arab public has sensed a loss of dignity and of the ability to make free decisions. True independence was traded in for western military, financial and political support. That intimate relationship distorted Arab politics. Reliant on foreign nations’ largesse and accountable to their judgment, the narrow ruling class became more responsive to external demands than to domestic aspirations.

Alienated from their states, the people have in some cases searched elsewhere for guidance. Some have been drawn to groups such as Hamas, Hezbollah and the Muslim Brotherhood, which have resisted and challenged the established order. Others look to non-Arab states such as Turkey, which under its Islamist government has carved out a dynamic, independent role, or Iran, which flouts western threats and edicts.

The breakdown of the Arab order has upended natural power relations. Traditional powers punch below their weight, and emerging ones, such as Qatar, punch above theirs. Al-Jazeera has emerged as a fully fledged political actor because it reflects and articulates popular sentiment. It has become the new Nasser. The leader of the Arab world is a television network.

Popular uprisings are the latest step in this process. They have been facilitated by a newfound fearlessness and feeling of empowerment – watching the US military’s struggles in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as Israel’s inability to subdue Hezbollah and Hamas, Arab peoples are no longer afraid to confront their own regimes.

For the US, the popular upheaval lays bare the fallacy of an approach that relies on Arab leaders who mimic the west’s deeds and parrot its words, and that only succeeds in discrediting the regimes without helping Washington. The more the US gave to the Mubarak regime, the more it lost Egypt. Arab leaders have been put on notice: A warm relationship with the United States and a peace deal with Israel will not save you in your hour of need.

Injecting economic assistance into faltering regimes will not work. The grievance Arab peoples feel is not principally material, and one of its main targets is over-reliance on the outside. US calls for reform will likewise fall flat. A messenger who has backed the status quo for decades is a poor voice for change. Attempts to pressure regimes can backfire, allowing rulers to depict protests as western-inspired and opposition leaders as foreign stooges.

Some policymakers in western capitals have convinced themselves that seizing the moment to promote the Israeli-Palestinian peace process will placate public opinion. This is to engage in both denial and wishful thinking. It ignores how Arabs have become estranged from current peace efforts; they believe that such endeavours reflect a foreign rather than a national agenda. And it presumes that a peace agreement acceptable to the west and to Arab leaders will be acceptable to the Arab public, when in truth it is more likely to be seen as an unjust imposition and denounced as the liquidation of a cherished cause. A peace effort intended to salvage order will accelerate its demise.

The Arab world’s transition from old to new is rife with uncertainty about its pace and endpoint. When and where transitions take place, they will express a yearning for more assertiveness. Governments will have to change their spots; their publics will wish them to be more like Turkey and less like Egypt.

For decades, the Arab world has been drained of its sovereignty, its freedom, its pride. It has been drained of politics. Today marks politics’ revenge.

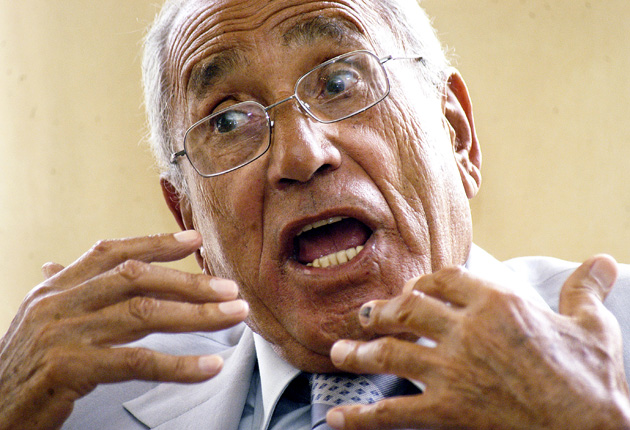

Mohamed Heikal: ‘I was sure my country would explode. But the young are wiser than us’: The Independent

Robert Fisk meets the doyen of Egypt’s journalists

Tuesday, 15 February 2011

The old man’s voice is scathing, his mind like a razor, that of a veteran fighter, writer, sage, perhaps the most important living witness and historian of modern Egypt, turning on the sins of the regime that tried to shut him up forever. “Mubarak betrayed the republican spirit – and then he wanted to continue through his son Gamal,” he says, finger pointed to heaven. “It was a project, not an idea; it was a plan. The last 10 years of the life of this country were wasted because of this question, because of the search for inheritance – as if Egypt was Syria, or Papa Doc and Baby Doc in Haiti.”

At 87, Mohamed Heikal is the doyen, the icon – for once the cliché is correct – of Egyptian journalism, friend and adviser and minister to Nasser and to Sadat, the one man who has predicted for 30 years the revolution that he has, amazingly, lived to see.

We didn’t believe him. For three decades, I came here to see Heikal and he predicted the implosion of Egypt with absolute conviction, outlining in devastating detail the corruption and violence of the Mubarak regime, and its inevitable collapse. And sometimes I wrote cynically about him, sometimes humorously, occasionally – I fear – patronisingly, rarely as seriously as he deserved. Yesterday, he offered me a cigar and invited me to say if I thought I was still right. No, I said, I was wrong. He was right.

Heikal in old age is a man of such eloquence, such energy, with such a vast memory, that men and women who are younger – a quality he much admires, and which won Egypt’s revolution last week – must be silent in his presence. “I lost the most important thing in my life,” he says with painful candour. “I lost my youth. I would love to have been out with those young people in the square.”

But Heikal is a wily beast. He was here for the Nasser revolution of 1952 and remembers the folly of power displayed by Egypt’s dictators. “I was completely sure there was going to be an explosion,” he says. “What stunned me was the movement of the millions. I was not sure I was going to live to see this day. I was not sure I was going to see the rising of the people.

“My old friend Dr Mohamed Fawzi came to see me a few days ago and said: ‘The balloon of lies is getting bigger every day. It will explode with the prick of a pin – and God save us when it explodes.’ Then the people came and filled the vacuum.

“I was worried that there would be chaos. But a new generation in Egypt came along, wiser than us a million times over, and they behaved in a moderate, intelligent way. There was no vacuum. The explosion didn’t happen.

“What I am worried about is that everything came as a surprise, and nobody is ready for what comes next. Nobody wants to give time for the air to clear. In these circumstances, you can’t take the right decisions. These people carry with them huge aspirations. The Americans and Israel and the Arab world are all pushing. Even the Military Council were not prepared for this. I say: give yourself time to sleep at last.

“Mubarak kept us all in suspense,” he goes on. “He was like Alfred Hitchcock, a master of surprise. But this was an Alfred Hitchcock situation without a plot. The man was improvising every day – like an old fox. The millions moved. I watched him – and I was stunned.

“In this grave situation, the regime got into contact with some people in the square, and it asked them if some delegation of powers from Mubarak to the Vice-President would be acceptable, and the people they were talking to said: ‘Maybe, yes.’ And so Mubarak thought he could make his speech on Thursday night because he was sure he had got an ‘OK’ from the square. I couldn’t believe my ears.”

Heikal was pleased that Mubarak delayed the crisis by remaining silent while the crowds built up in Tahrir Square. “In those 18 days, something very important happened. We started with about 50-60,000 people. But as Mubarak delayed and prevaricated like the old fox he is, it gave the chance for the people to come out. This changed the whole equation. Six days into the crisis, Mubarak simply didn’t understand what had happened.”

Heikal bemoans the wasted years and the deaths of the past three weeks – “our revolution was a great historical tragedy,” he says – and does not yet see the nature of post-revolutionary Egypt. “I am happy with the presence of the army – but I want the presence of the people, too. The people are bewildered about what they have achieved.”

On Saturday night, Heikal was invited, for the first time in almost three decades, to appear once more on Egyptian state television. His reply was as feisty as it was when Sadat offered him the job of chief of the National Security Council after Nasser’s death. “I told Sadat that if we differed as we did when I was a newspaperman on Al-Ahram, how could I lead his National Security Council?” So when the government television asked him to appear this weekend, Heikal replied: “I was prevented by government order from appearing for 30 years and now you tell me that the doors are open again. I was prevented from appearing by government order, and now I am supposed to come by invitation.”

A few months ago, after Heikal had visited Lebanon and met Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah, the Hezbollah leader, a furious Egyptian Foreign Minister turned up at Heikal’s farm in the Nile Delta. “Do you think you represent the Egyptian people?” the minister shouted at him. Heikal asked the minister: “Do you think you represent the Egyptian people?”

The lines look good on Heikal’s face, a wise old bird as well as wily. But he’s a bit hard of hearing and feels it necessary to apologise for his 87 years, a young man trapped in an old man’s body. And anyone invited to his inner sanctum above the Nile, full of books and beautiful carpets and the smell of fine cigars, can see Heikal’s sadness.

“The difference between Mubarak and me is that I never tried to hide my age,” he says. “He did. He dyed his hair. So whenever he looked in the mirror, he saw Mubarak as a young man. But all old men have vanity. When I was young and was on television, I used to ask my friends: ‘Did I say the right thing?’ Now I ask them: ‘How did I look?” For The Independent’s post-revolutionary portrait of the great man, he whipped off his spectacles. “Vanity!” he cried.

Mubarak, he believes, was terrified that government files would be released if he resigned, that the regime’s secrets would come tumbling out. “What I’m afraid of is that the dishonesty of some of the politicians in Egypt will tarnish such a valuable event,” Heikal says. “They will use the issue of accountability to settle accounts. I want this country to have a proper investigation, not throw these files away for people to use for their own agenda. It is opportunism by politicians that I am afraid of. All the [regime’s] files should be opened. An account should be given to our people for the last 30 years – but it should not be a matter for revenge. If small politicians use this, it will affect the value of what must be done.”

Historically, Heikal regards the events of the past three weeks as overwhelming, unstoppable, unprecedented.

“In revolutions, there is no pattern. People want a change from a present to a future. Every revolution is conditioned by where it starts and where it is moving. But this event showed a huge Egyptian mass of people that it is possible to defy the terror of the state. I think this will revolutionise the Arab world.”

Locked up by Anwar Sadat shortly before his assassination, Heikal was released from prison by Mubarak, and I recalled that we met within hours of his release, when he – Heikal – was grateful to Mubarak, and sang his praises. “Yes, but as a man of transition,” he replied. “I thought he would be President only a short time. He came from the Egyptian military, a national and loved institution. He saw Sadat being killed by his own people – he was present when this happened – and I thought he must have learned a tragic lesson about the Egyptian people when their patience runs out. I thought he could be a good bridge for the future.

“In the last document that Nasser wrote on 30 March 1968, he promised that after the 1967 war, his role must end. ‘The people proved to be more powerful than the regime,’ he wrote. ‘The people have become bigger than the regime.’

“But everyone forgets. Once you enjoy power and the sea of quietness that comes with it, you forget. And day after day, you discover the privileges of power.

“Now we have semi-politicians who want to take advantage of this revolution. Some contenders are already promoting themselves. But the system has to be changed. The people made known what they want. They want something different. All the most modern technology in the world was used in this uprising. The people want something different.”

Heikal saw me to the door of the lift, shook hands courteously, eyebrows raised. Yes, I repeated. He was right.

Egypt crisis: Army sets constitution reform deadline: BBC

The military is trying to quell strikes and protests still being held around the country

Egypt’s ruling military council has announced that work on reforming the country’s constitution is to be completed in 10 days.

A committee led by a retired judge has been tasked with proposing legal changes, said the council.

It earlier suspended the current constitution, which was amended during ousted President Hosni Mubarak’s tenure to strengthen his grip on power.

Mr Mubarak stepped down last week after more than two weeks of protests.

The higher military council – which assumed power after Mr Mubarak stepped down – said on Tuesday that the amended constitution would be put to a popular referendum.

The eight-member committee is mostly made up of experts in constitutional law but it includes a senior figure from the opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood.

It is headed by Tariq el-Bishri, considered one of Egypt’s top legal minds, and on Tuesday held its opening meeting with Defence Minister Mohamed Hussein Tantawi.

The committee is instructed to “amend all articles as it sees fit to guarantee democracy and the integrity of presidential and parliamentary elections”.

Strikes ease

The BBC’s Jon Leyne in Cairo says it looks as if the military council is fulfilling its pledge to hand the country back to civilian rule as quickly as possible.

Tahrir Square, the focus of protests in Cairo, has largely returned to normal

The speed of the move will reassure the opposition, he says, although there might be some nervousness about whether it is an attempt to push through changes in too much of a rush.

The military council has also repeated its calls for an end to strikes that spread across the country during Sunday and Monday.

The stoppages are dealing a further blow to Egypt’s ailing economy, damaged by three weeks of unrest.

“The supreme council is aware of the economic and social circumstances society is undergoing, but these issues cannot be resolved before the strikes and sit-ins end,” the state news agency Mena quoted the military as saying.

“The result of that will be disastrous,” it added.

Strikes eased on Tuesday, mainly because offices and businesses were closed for an Islamic holiday.

But correspondents said some smaller protests continued in provinces outside Cairo, mainly called by workers demanding higher pay.

Meanwhile, Mr Mubarak, 82, is reported to be in poor health in his residence in the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh.

The Saudi-owned daily newspaper Asharq al-Awsat said on Tuesday that the former president’s health was “declining drastically” and he was refusing to travel abroad for treatment. The paper quoted a former security official linked to the military high command.

In his final speeches to the nation, Mr Mubarak said that he would die in Egypt. He has not been seen in public since stepping down.

On Tuesday, the Egyptian ambassador to the US told American TV network NBC that Mr Mubarak was in poor health.